Generics make up 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. - and they save patients and the system billions every year. But behind that number is a quiet reality: not all generics are created equal. For pharmacists, spotting the ones that might harm patients isn’t optional - it’s part of the job. When does a generic drug stop being a cost-saving win and start becoming a risk? Here’s what to watch for.

Therapeutic equivalence isn’t always guaranteed

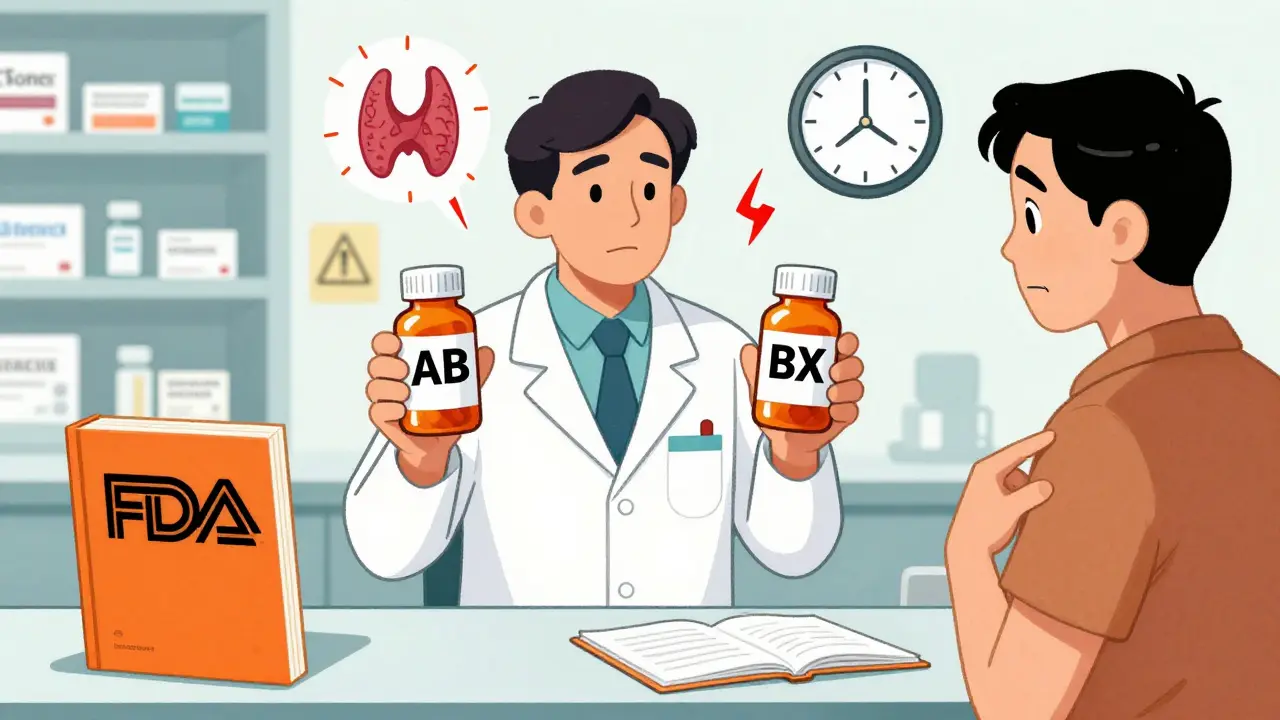

The FDA says generics must be bioequivalent to brand-name drugs. That means their absorption rate - how much of the drug enters your bloodstream - has to fall within 80% to 125% of the original. Sounds tight, right? But here’s the catch: that 45% window is wide enough to cause real problems for certain drugs. Take levothyroxine. A patient stabilized on one generic manufacturer might switch to another - maybe because the pharmacy changed suppliers or insurance pushed a cheaper option - and suddenly their TSH levels spike from 2.1 to 8.7. That’s not a fluke. It’s a documented pattern. The FDA’s Orange Book lists over 14,800 generic products, but 10.3% of them carry a 'BX' rating - meaning they’re not rated as therapeutically equivalent. That’s your first red flag.NTI drugs are where things get dangerous

Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs are the ones that can’t afford variation. Even a small change in blood levels can mean the difference between healing and harm. The FDA has identified 18 NTI drugs that need special attention. Among them: warfarin, phenytoin, cyclosporine, and digoxin. Digoxin alone has 12.7 adverse events per 10,000 prescriptions when switching manufacturers - more than double the rate of non-NTI drugs. Why? Because the margin between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. A patient on digoxin might feel fine on one generic, then start vomiting, seeing halos around lights, or develop dangerous heart rhythms after a switch. Pharmacists who’ve seen this know: if a patient’s lab values suddenly drift after a generic change - especially with an NTI drug - don’t assume it’s noncompliance. Question the drug first.Extended-release and complex formulations are trouble spots

It’s not just about the active ingredient. How the drug is delivered matters. Extended-release (ER) tablets, transdermal patches, inhalers, and injectables are far harder to copy than a simple pill. The FDA found that 7.2% of generic ER opioids failed dissolution testing - meaning they didn’t release the drug properly over time. That’s compared to just 1.1% of immediate-release versions. A patient on ER diltiazem might get a new bottle that looks identical - same color, same markings - but the tablet dissolves too fast. Instead of 12 hours of steady blood pressure control, they get spikes and crashes. The FDA reported 47 cases of therapeutic failure linked to one generic version of diltiazem CD between 2021 and 2022. Pharmacists who track manufacturer names on prescriptions can trace these patterns. If a patient says, “This one doesn’t work like the last one,” don’t brush it off. Check the label. Note the manufacturer. Log it.

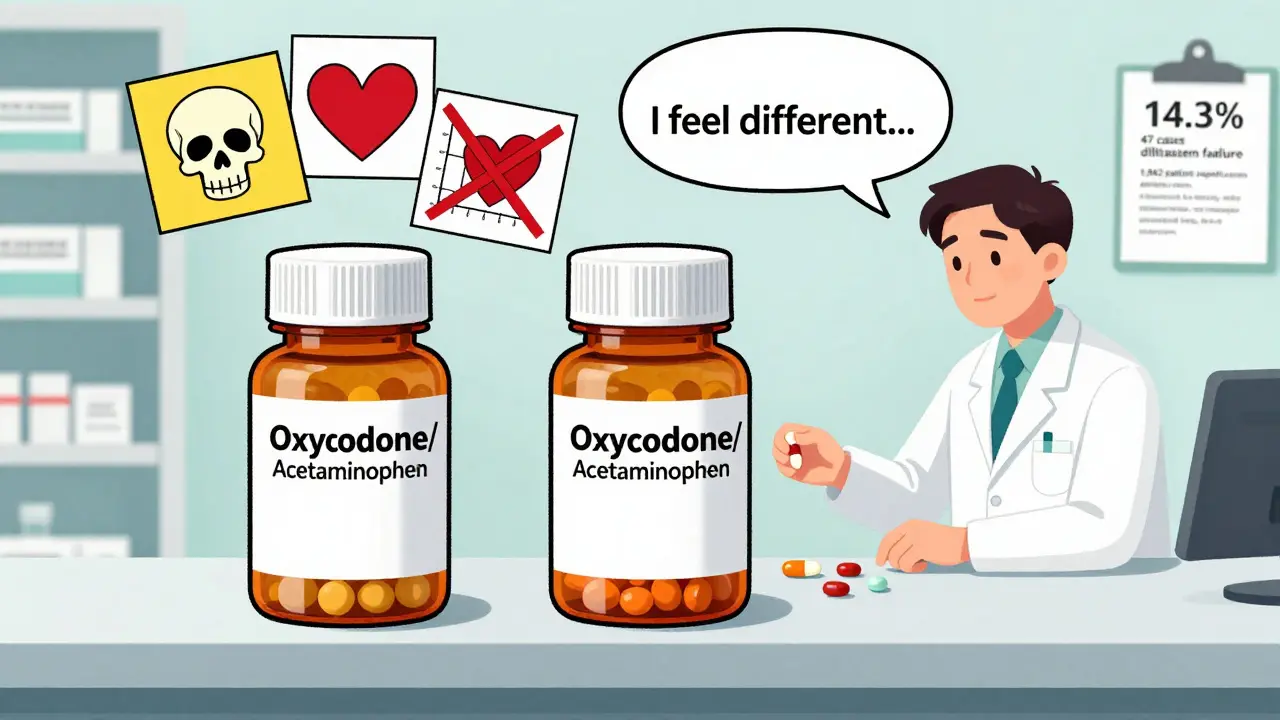

Look-alike, sound-alike names cause confusion

It sounds like a joke, but it’s deadly serious. Oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen? The names are almost identical. So are the pills. A pharmacy technician grabs the wrong one. A patient gets the wrong painkiller. Or worse - a patient on warfarin gets a generic with a similar-looking bottle and label as another anticoagulant. That’s not rare. According to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 14.3% of all generic medication errors come from this kind of confusion. Pharmacists who’ve worked in high-volume settings know: the more similar the packaging, the higher the risk. If two generics from different manufacturers look almost identical - same shape, same color, same imprint - that’s a setup for disaster. Flag it. Report it. Push for better labeling.Patients are speaking up - listen to them

Patients notice when things change. They might not know the science, but they know their body. “I feel jittery now.” “I can’t sleep like before.” “My stomach’s been off since I switched.” A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found that 22.4% of patients reported different side effects after switching generic manufacturers. The FDA’s own Patient-Focused Drug Development program received 1,842 submissions between 2020 and 2023 about inconsistent effectiveness or unexpected side effects. That’s not noise - that’s data. And pharmacists are the ones who hear it firsthand. If a patient says, “The last one worked fine,” and this one doesn’t - believe them. Don’t assume it’s psychological. Don’t assume it’s adherence. Check the manufacturer. Check the dose. Check the formulation. And if the patient’s symptoms align with known issues - like GI upset with delayed-release omeprazole or mood changes with fluoxetine - document it. That’s how patterns emerge.

What pharmacists should do - step by step

You don’t need to be a pharmacokinetics expert to spot trouble. Here’s what works:- Check the Orange Book - before dispensing. Look for 'AB' (therapeutically equivalent) versus 'BX' (not equivalent). If it’s BX, don’t substitute without consulting the prescriber.

- Record the manufacturer - every time. Use your pharmacy system to log the manufacturer name. That way, if a patient has a reaction, you can trace it. Studies show 68.4% of therapeutic failure investigations require this data.

- Watch for NTI drugs - levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus. If a patient’s lab values change after a switch, suspect the generic before anything else.

- Listen to patient reports - don’t dismiss “I feel different.” Ask: When did it start? What changed? Was it a new generic?

- Report adverse events - use the FDA’s MedWatch app. It takes under five minutes. Your report helps the agency catch dangerous patterns before more people get hurt.

- Know your state laws - 29 states require substitution unless the prescriber says no. But 4 states (Massachusetts, New York, Texas, Virginia) have special rules for NTI drugs. Know yours.

It’s not about distrust - it’s about vigilance

Most generics are safe. Most are effective. Most save lives by making treatment affordable. But the system isn’t perfect. Regulatory standards are designed for mass production, not individual variation. And when you’re dealing with drugs where 20% variation can mean hospitalization - that’s not just a statistic. It’s a patient’s reality. Pharmacists aren’t gatekeepers. We’re the last line of defense. When a patient walks in with a new prescription for a generic, you’re not just filling a bottle. You’re checking if the medicine they’re about to take will do what it’s supposed to - without making them sick. That’s why flagging issues isn’t extra work. It’s the job.Can generic drugs be less effective than brand-name drugs?

Yes - but only in specific cases. Most generics work just as well. However, for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin, even small differences in absorption can lead to therapeutic failure. The FDA allows up to a 20% variation in bioavailability, which is acceptable for many drugs but dangerous for others. When patients report unexplained changes in symptoms or lab values after switching generics, the drug itself should be the first suspect.

How often do pharmacists encounter problematic generics?

A 2022 survey of 1,247 pharmacists found that 63.2% had encountered at least one problematic generic substitution in the past year. Of those, nearly 29% reported incidents that led to patient harm - including hospitalizations, lab abnormalities, or worsening symptoms. These aren’t rare outliers. They’re common enough that every community and hospital pharmacist should have a protocol for tracking and reporting them.

What’s the difference between AB and BX ratings in the FDA Orange Book?

The FDA Orange Book rates generic drugs as either 'AB' or 'BX'. 'AB' means the generic is therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug - it has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, route, and bioequivalence. 'BX' means the FDA does not consider it equivalent. This could be due to unresolved bioequivalence concerns, different delivery systems (like extended-release), or lack of adequate data. Pharmacists should never substitute a BX-rated drug unless the prescriber explicitly allows it.

Why are extended-release generics more likely to cause problems?

Extended-release (ER) formulations rely on complex technologies - like coatings, matrices, or osmotic systems - to slowly release the drug over hours. These are harder to replicate than simple tablets. Studies show 7.2% of generic ER opioids failed dissolution testing, meaning they didn’t release the drug as intended. A patient might get a full dose all at once (risking overdose) or not enough over time (leading to withdrawal or loss of control). This is why ER drugs, especially opioids, benzodiazepines, and antihypertensives, require extra scrutiny.

Should pharmacists refuse to substitute a generic if a patient says it doesn’t work?

Yes - and here’s how: First, listen. Document the patient’s report. Check the manufacturer and compare it to their previous prescription. If it changed, contact the prescriber. Many states allow pharmacists to consult with prescribers before substituting, even under mandatory substitution laws. For NTI drugs, most prescribers will agree to stick with the original brand or generic. Patient safety always overrides cost or policy.

Are generic drugs from foreign manufacturers more likely to be problematic?

The FDA inspects foreign manufacturing facilities, and in 2022, 63.2% of quality issues found during inspections were in India, and 24.7% in China. While most foreign-made generics are safe, the higher rate of inspections and citations suggests increased risk. Pharmacists should pay attention to manufacturer origin - especially if a new generic from a previously unfamiliar company suddenly appears on the shelf. If multiple patients report issues with the same foreign-made product, report it to the FDA.

All Comments

Jason Pascoe February 12, 2026

Been a pharmacist for 18 years, and this post nails it. I’ve had patients come in saying, ‘This new pill makes me feel like I’m on a rollercoaster.’ Turns out, they switched from Teva to Mylan levothyroxine. TSH went from 1.9 to 7.1 in three weeks. We switched ‘em back. No drama. Just common sense.

Log the manufacturer. Every. Single. Time. It’s not extra work-it’s your liability shield and your patient’s lifeline.