When you switch pharmacies, it’s not just about picking a new location or getting better prices. It’s about making sure your medications-especially if they’re controlled substances-move safely and legally from one pharmacy to another. If you’ve ever waited days for a refill because the transfer got stuck, you know how frustrating it can be. But with the right information, you can avoid delays and confusion. The rules changed in August 2023, and now the process depends heavily on what kind of medication you’re taking.

What You Need to Give the New Pharmacy

At a minimum, the new pharmacy needs your full legal name, date of birth, and current address. That’s standard for any prescription transfer, whether it’s for blood pressure pills or antibiotics. But if you’re switching for a controlled substance, like Adderall, oxycodone, or Xanax, you need to be more specific. You’ll need the exact name of the medication, the dosage, how often you take it, your prescriber’s name, and the prescription number. Don’t assume they’ll know which one you mean-even small differences in dosage or brand vs. generic matter.

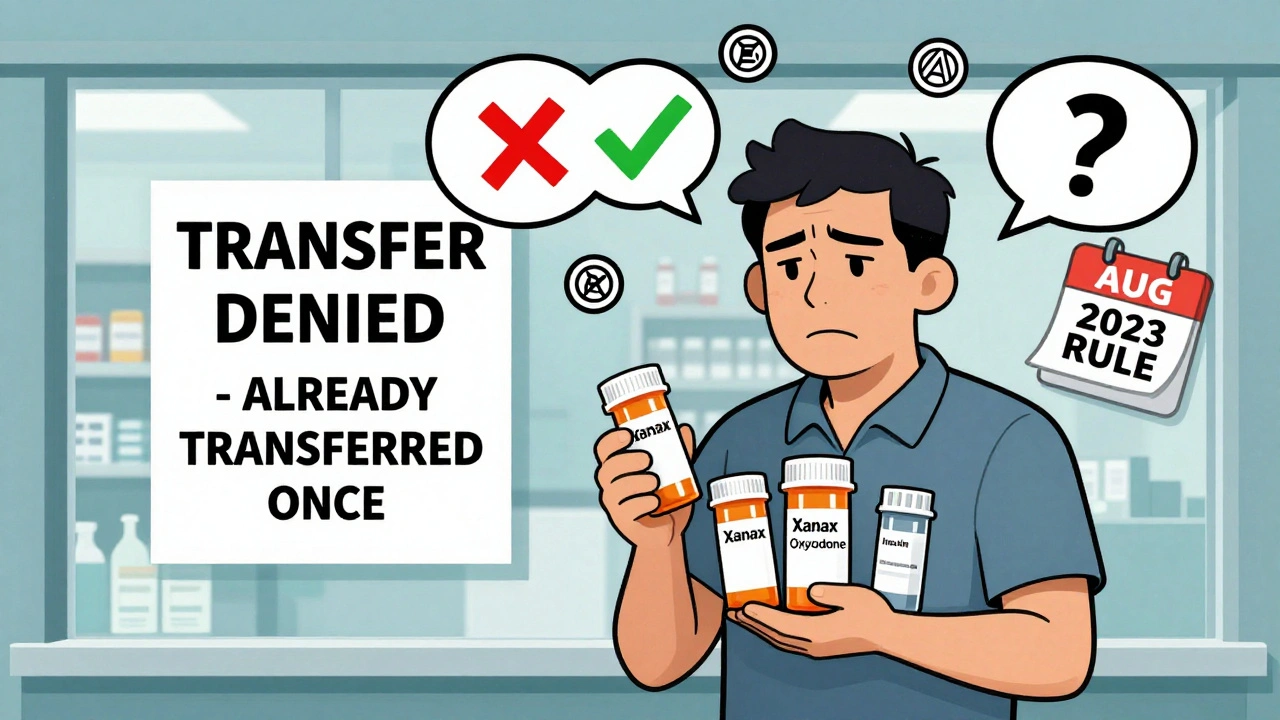

For non-controlled medications (like insulin, statins, or thyroid meds), you can usually transfer multiple times as long as refills are left. But for controlled substances, the rules are strict. Under the DEA’s August 2023 Final Rule, you can only transfer a prescription for a Schedule III, IV, or V controlled substance one time between pharmacies. After that, you must get a new prescription from your doctor. Schedule II drugs-like oxycodone tablets or fentanyl patches-can’t be transferred at all. If you need a refill and your pharmacy changes, you have to go back to your prescriber.

How the Transfer Actually Works

The transfer isn’t something you do yourself. You give the new pharmacy your old pharmacy’s name and phone number. Then they call or send a secure electronic message to the old pharmacy. The old pharmacy confirms the prescription details and sends the data directly to the new one. The prescription must stay electronic. No paper copies, no screenshots, no photos. Even if you have a printed prescription, the transfer must happen through a DEA-compliant electronic system.

Both pharmacists have to document everything. The transferring pharmacist must mark the original prescription as “VOID” in their system and record the name of the receiving pharmacy, its DEA number, the date of transfer, and their own name. The receiving pharmacist must add “TRANSFER” to the prescription record, include the original pharmacy’s info, and log their own name and the transfer date. All records must be kept for two years. If any of this isn’t done right, the transfer can be rejected-even if the prescription is valid.

Why Controlled Substances Have Tighter Rules

The DEA tightened these rules to prevent drug diversion. Before August 2023, patients had to go back to their doctor every time they switched pharmacies to get a new prescription. That was inconvenient, but it also acted as a check. The new rule lets you transfer electronically without seeing your doctor again-but only once. That’s a balance: convenience for patients, but a hard stop to stop people from “pharmacy hopping” to get extra pills.

Some people think this rule is unfair. For example, if you move across town and your old pharmacy closes, you still can’t transfer your Adderall prescription to the new one nearby if you’ve already transferred it once. The DEA says it’s per prescription, not per patient. So if you have three different controlled prescriptions, you can transfer each one once to different pharmacies. But each individual prescription gets only one shot.

What Happens If a Transfer Gets Refused

It happens more often than you’d think. A Consumer Reports survey in September 2023 found that 68% of people who tried to transfer a prescription ran into problems. The biggest issue? Controlled substance limits. About 42% of complaints were about being told they couldn’t transfer because the prescription had already been moved once. Another 31% were due to missing or incorrect information-like a wrong prescriber DEA number or mismatched date of birth.

Some pharmacies refuse transfers based on state laws that are stricter than federal rules. For example, a pharmacy in California might reject a transfer from a pharmacy in Arizona if the state doesn’t have a reciprocity agreement. Rural pharmacies with outdated software may not even be able to process electronic transfers. If your transfer is denied, ask for the reason in writing. Pharmacies are required to give you a valid explanation under federal law.

How Long Does It Take?

Most non-controlled transfers take 24 to 48 hours if the pharmacies are in the same network. Controlled substance transfers can take longer-up to three business days-because of extra verification steps. If your old pharmacy is slow to respond or the new one doesn’t have the right system, it can drag on. That’s why it’s smart to start the process at least a week before you run out. Don’t wait until your last pill is gone.

What to Do Before You Switch

- Check if your medication is a controlled substance. Ask your doctor or look up the drug on the DEA’s website. Schedule II, III, IV, and V are controlled. Most others aren’t.

- Call your current pharmacy and ask how many refills you have left. If you’re out, you’ll need a new prescription regardless of transfer rules.

- Call the new pharmacy first. Ask if they accept electronic transfers for controlled substances. Not all do, especially smaller or independent pharmacies.

- Have your prescription details ready: drug name, dosage, prescriber name, prescription number, and refill count.

- If you’re transferring multiple prescriptions, do them one at a time. Don’t expect all of them to go through at once.

What Doesn’t Work

You can’t transfer a prescription that’s already been filled and used up all its refills. You can’t transfer a Schedule II drug, no matter what. You can’t fax a photo of your prescription. You can’t ask your doctor to email the prescription to the new pharmacy unless they send it through an approved EPCS system. And you can’t transfer a prescription that’s expired-even if you still have refills left.

What’s Changing in the Future

The DEA plans to review the one-time transfer rule in 2024. Industry experts think it might become possible to transfer controlled prescriptions more than once in the next few years, especially as data shows patients aren’t abusing the system. But for now, the rule stands. Meanwhile, more pharmacies are upgrading their systems. As of Q3 2023, 92% of controlled substance prescriptions in the U.S. were transmitted electronically. That means most transfers should now go smoothly-if you give the right info.

Bottom Line

Switching pharmacies doesn’t have to be a headache. If you’re taking regular medications, the process is simple. Just give the new pharmacy your details and let them handle the rest. But if you’re on a controlled substance, treat it like a legal document. Know the rules. Know your prescription status. Ask questions. And don’t assume the pharmacy will know what you need. The system works-if you give it the right pieces.

Can I transfer a prescription for a Schedule II drug like oxycodone to a new pharmacy?

No. Under current DEA regulations, Schedule II controlled substances cannot be transferred between pharmacies under any circumstances. If you need to switch pharmacies, you must get a new prescription from your prescriber. This rule is strict and applies nationwide.

How many times can I transfer a controlled substance prescription?

For Schedule III, IV, or V controlled substances, you can transfer the prescription only one time between pharmacies. After that, you must get a new prescription from your doctor. This applies per prescription, not per patient. So if you have three different controlled prescriptions, you can transfer each one once, but not more than once for each.

What if my old pharmacy won’t release my prescription?

The old pharmacy is legally required to transfer the prescription if it’s valid and has refills remaining. If they refuse, ask for the reason in writing. Common reasons include expired prescriptions, no refills left, or missing documentation. If the refusal seems unjustified, you can contact your state pharmacy board for help.

Can I transfer prescriptions across state lines?

Yes, but it’s more complicated. Federal rules allow interstate transfers, but state laws vary. Some states have reciprocity agreements with others; some don’t. If you’re moving to a new state, check with the new pharmacy first. They may need to verify compliance with local regulations before accepting the transfer.

Do I need to bring my old prescription bottle to the new pharmacy?

No. You don’t need to bring the bottle. The transfer is done electronically between pharmacies. But having the bottle handy can help you confirm the medication name, dosage, and prescriber details-especially if your memory is unclear. It’s useful, but not required.

What if I run out of refills before the transfer completes?

If you run out before the transfer is done, you’ll need to contact your prescriber for a new prescription. You can’t get a refill at the new pharmacy until the transfer is complete and confirmed. Plan ahead-start the transfer at least a week before you expect to run out.

Are there any fees for transferring prescriptions?

No. Federal law prohibits pharmacies from charging patients for transferring prescriptions. If a pharmacy asks for a fee, it’s against regulations. You can report this to your state pharmacy board or the DEA.

All Comments

David Palmer December 11, 2025

Bro just walked into a pharmacy last week and they said they couldn't transfer my Adderall because it was already moved once. I had to drive 40 minutes to see my doc. Wtf is this? I'm not a drug dealer.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt December 12, 2025

Man, I feel you. I used to think this stuff was just red tape until my grandma couldn't get her Xanax transferred after moving to assisted living. The system's broken, but at least now there's a paper trail. Maybe one day they'll fix it so we don't have to play pharmacy roulette.

Taylor Dressler December 12, 2025

For anyone confused about Schedule II vs. III-IV-V: Schedule II (like oxycodone, fentanyl) = NO transfers. Schedule III-V (like Adderall, Xanax, Vicodin) = ONE transfer only. After that, new script required. It's not arbitrary-it's federal law to prevent diversion. The DEA didn't make this up to annoy you. It's because people were gaming the system. I work in pharmacy compliance-this saves lives.

Katherine Liu-Bevan December 13, 2025

My mom had to switch pharmacies after her old one closed. She was on three controlled meds-each got one transfer. She called the new pharmacy ahead, had her script numbers ready, and it went smoothly. The key? Don’t wait until day 30 to start. Call a week before you run out. And don’t assume they’ll know what you mean-say the exact dosage and brand. Generic vs. brand can trip them up.

matthew dendle December 14, 2025

so uhm like... the dea says you can only transfer once?? like wtf is this 1987?? they think we're all junkies?? i just wanna get my meds without playing detective with my own prescriptions

Mia Kingsley December 15, 2025

Okay but why does my pharmacy keep saying 'we can't transfer' when I clearly have refills?? I showed them the bottle, I gave them the script #, I even printed the DEA guidelines!! They just shrug and say 'policy'... I think they're just lazy and don't wanna call the other pharmacy. They don't care if I'm in pain.

Kaitlynn nail December 16, 2025

It's not about control-it's about containment. We're not in a free-market pharmaceutical utopia anymore. The system's designed to protect you from yourself, even if it feels like a hassle. Think of it as emotional insurance.

Courtney Blake December 17, 2025

Let me guess-this rule only applies to Americans. In Canada, they just fax it and call it a day. We don't need this bureaucratic nonsense. Why are we letting the DEA run our lives like we're in a dystopian prison?

Ben Greening December 18, 2025

As a long-time pharmacy technician, I can confirm: 90% of transfer failures come from incomplete or mismatched data. Date of birth off by one digit? Prescriber DEA number typo? Pharmacy system glitch? All it takes is one error and the whole thing gets rejected. It’s not the pharmacy being difficult-it’s the data being sloppy. Always double-check your info before calling.

Stephanie Maillet December 18, 2025

It’s interesting how we’ve built a system that prioritizes safety over convenience… but then makes it so hard to actually be safe. If the goal is to prevent abuse, why not allow multiple transfers with real-time DEA tracking? Why force people to jump through hoops instead of using tech to solve the problem? We have the tools-why not use them?

Jean Claude de La Ronde December 19, 2025

So the DEA says 'one transfer only'... but if you move across the country, you're supposed to get a new script from your old doctor who you haven't seen in 6 months? That's not a rule-it's a joke. Next they'll make us send a notarized letter asking for our insulin. This isn't healthcare. It's performance art.

Ariel Nichole December 21, 2025

Just wanted to say thanks for the clear breakdown. I was so stressed about switching pharmacies for my thyroid med and my Adderall. Now I know to call ahead, check refills, and not panic if the transfer takes a few days. Seriously, this post saved me a lot of anxiety.

john damon December 22, 2025

Just transferred my Xanax 🎉🎉🎉 and it took 2 hours. New pharmacy was awesome. Old one? Barely answered the phone. Pro tip: if they sound annoyed, hang up and call back later. Or just go to CVS. They always know what’s up 💪💊