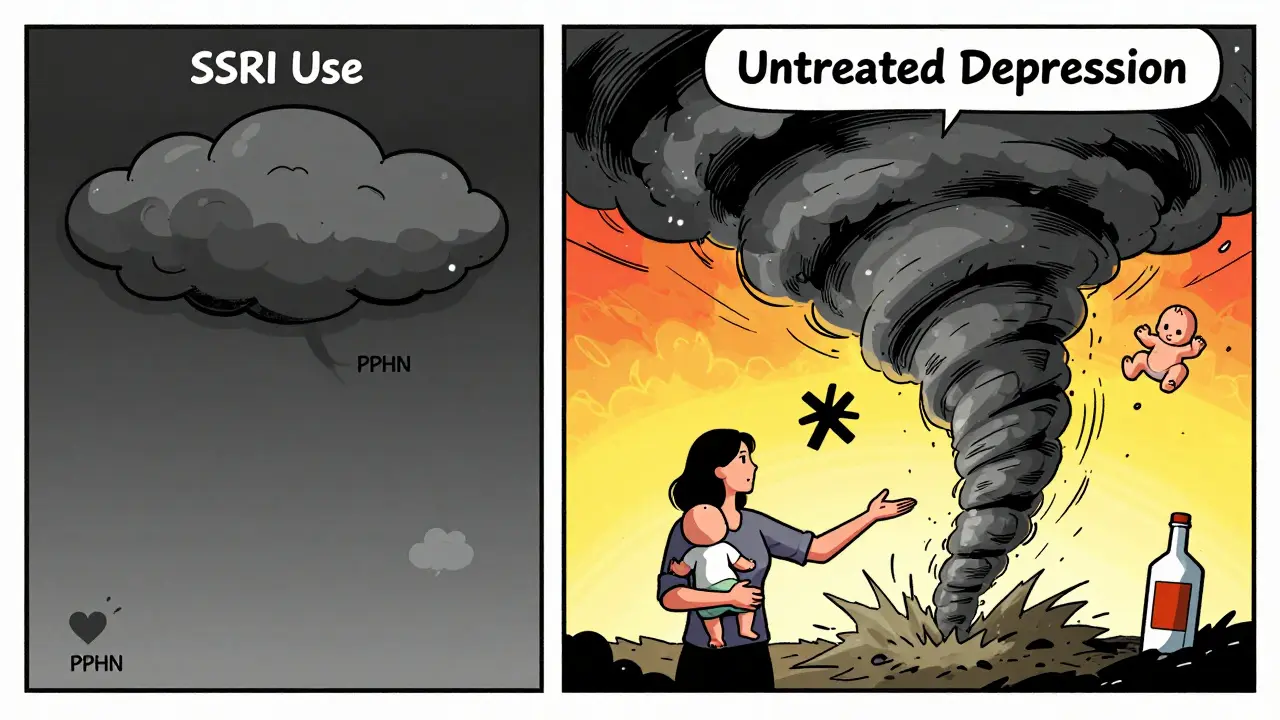

When a woman is pregnant and struggling with depression or anxiety, the decision to take an SSRI isn’t simple. On one side, there’s the real danger of untreated mental illness - suicide, preterm birth, poor bonding with the baby. On the other, there are questions about possible risks to the baby: heart defects, breathing problems, long-term development. The truth? For many women, continuing an SSRI during pregnancy is the safer choice. But it’s not one-size-fits-all. Here’s what actually matters.

Why Untreated Depression Is Riskier Than SSRIs

Let’s start with the facts most people overlook: untreated depression during pregnancy is far more dangerous than taking an SSRI. The CDC found that suicide accounts for 20% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. That’s not a rare tragedy - it’s a leading cause of death for pregnant and postpartum women. Depression also doubles the risk of preterm birth. Women with untreated depression are 2.2 times more likely to deliver early than those without. And that’s not all - they’re 25% more likely to use alcohol or drugs during pregnancy, and their babies are 30% less likely to form a secure emotional bond after birth.

Now compare that to the effects of SSRIs. A 2022 study in JAMA Psychiatry showed that women who stopped their SSRI during pregnancy had a 92% chance of their depression returning. Those who stayed on medication? Only 21% relapsed. That’s not a small difference - it’s life-or-death. If you’re already on an SSRI and your depression is moderate to severe, staying on it often prevents worse outcomes than stopping.

Which SSRIs Are Safer in Pregnancy?

Not all SSRIs are the same. Some are recommended as first-line options. Others are avoided. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) agree on this:

- Sertraline (Zoloft) - First choice. It crosses the placenta less than other SSRIs, has the lowest risk of heart defects and PPHN, and is the most studied in pregnancy.

- Citalopram (Celexa) and Escitalopram (Lexapro) - Also considered safe. Avoid doses above 40mg/day due to potential QT prolongation.

- Fluoxetine (Prozac) - Second-line. It stays in the body longer, which can cause buildup in the baby. May be useful for women with severe, recurrent depression.

- Paroxetine (Paxil) - Avoid in the first trimester. Linked to a small but real increase in heart defects (from 0.5% to 0.7-1.0% risk).

Why does this matter? Because choosing the right one reduces risk. Sertraline has been studied in over 1.8 million births. No major increase in birth defects. No consistent link to long-term developmental issues. That’s not luck - it’s data.

The Real Risks: What Actually Happens?

Let’s talk numbers - not percentages, but real risks. People hear “SSRIs increase PPHN risk” and panic. But here’s what that means:

- Without SSRI use: 1-2 out of every 1,000 babies develop Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn (PPHN).

- With SSRI use in the third trimester: 3-6 out of 1,000.

That’s a doubling - but the absolute risk is still less than 1%. Compare that to the 10-15% of pregnant women who develop depression, and the 20% risk of maternal death from suicide. One is rare. The other is common. And both need attention.

Preterm birth? Studies show 12.5% of women on SSRIs deliver early, compared to 9.5% of depressed women not on medication. But here’s the twist: when researchers control for how severe the depression was, the difference shrinks to almost nothing. That means it’s not the SSRI causing preterm birth - it’s the depression itself.

Low birth weight? Apgar scores? These are slightly higher in SSRI-exposed babies - but again, the difference disappears when you account for depression severity. The medication isn’t the villain. The illness is.

What About Long-Term Effects on the Child?

This is where the debate gets noisy. Some studies say kids exposed to SSRIs in the womb are more likely to develop anxiety or depression later. Columbia University researchers found a 28% rate of depression by age 15 in these children - compared to 12% in kids whose mothers had depression but didn’t take SSRIs.

But here’s what those studies miss: they don’t fully separate genetics from medication. If a mother has depression, her child may inherit genes that make them more vulnerable to mood disorders. The SSRI might not be the cause - it might be the marker. A 2021 study in The Lancet looked at siblings where one was exposed to SSRIs and the other wasn’t. The risk difference vanished. That suggests genetics and environment, not the drug, are the real drivers.

The NIH’s 2023 review says it best: “Mixed evidence exists, but the risks of untreated maternal depression outweigh the uncertain risks of SSRI exposure.”

What If You Want to Stop Taking SSRIs?

Some women hear “SSRIs might be risky” and decide to quit. But quitting cold turkey is dangerous. A 2023 study in Obstetrics & Gynecology found that 73% of women who stopped abruptly had withdrawal symptoms - dizziness (42%), nausea (38%), and “brain zaps” (29%).

ACOG recommends tapering slowly - over 4 to 6 weeks - if you’re thinking of stopping. And never do it without checking in with your provider. Use the PHQ-9 screening tool weekly. If your score goes above 10, you’re at risk for relapse. And if you’re already feeling low? That’s a sign to keep going, not stop.

What Should You Do? A Clear Roadmap

If you’re pregnant or planning to be, here’s what to do:

- If you’re already on an SSRI and it’s working - stay on it. Switching meds mid-pregnancy increases relapse risk.

- If you’re not on one but have moderate to severe depression - talk to your doctor about starting sertraline. It’s the safest bet.

- Avoid paroxetine in the first trimester. It’s not worth the risk.

- Don’t stop without a plan. Taper slowly. Monitor your mood weekly.

- Use the lowest effective dose. Higher doses don’t mean better results - just more exposure.

- After birth, monitor your baby for neonatal adaptation syndrome (jitteriness, feeding trouble, irritability). It happens in 30% of cases - but it’s temporary and resolves in 2 weeks.

What’s Next? Research and Hope

The NIH just launched a $15 million study in September 2025 tracking 10,000 mother-child pairs to see how SSRI exposure affects kids into their teens. Results won’t come until 2030. But we already know enough to make smart choices today.

Future tools will help even more. Researchers are developing SSRIs with less placental transfer. Genetic tests for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 enzymes - which affect how your body processes these drugs - are already available. If you’re a slow metabolizer, you might need a lower dose. If you’re a fast one, you might need more. Personalized medicine is coming.

For now, the message is clear: SSRIs are not the enemy. Untreated depression is. For women with moderate to severe symptoms, the benefits of staying on medication far outweigh the risks. The goal isn’t to avoid all medication - it’s to choose the right one, at the right dose, with the right support.

Are SSRIs safe to take during pregnancy?

Yes, for most women with moderate to severe depression or anxiety. Large studies of over 1.8 million births show no major increase in birth defects with SSRIs like sertraline, citalopram, or escitalopram. The biggest risk isn’t the medication - it’s untreated depression, which raises the chance of suicide, preterm birth, and poor bonding with the baby.

Which SSRI is safest during pregnancy?

Sertraline (Zoloft) is the first-line choice. It has the lowest risk of heart defects and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). It crosses the placenta less than other SSRIs and has the most safety data from large population studies. Citalopram and escitalopram are also safe. Paroxetine should be avoided in the first trimester due to a small increase in heart defects.

Can SSRIs cause autism or long-term developmental problems?

Some early studies suggested a link, but newer research that controls for family history and depression severity shows no clear connection. A 2021 study in The Lancet found no increased autism risk when comparing siblings - one exposed to SSRIs, one not. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the NIH agree that current evidence doesn’t support a causal link between SSRIs and long-term neurodevelopmental issues.

What if I want to stop my SSRI during pregnancy?

Don’t stop suddenly. Abruptly stopping SSRIs leads to withdrawal symptoms in 73% of women - dizziness, nausea, and "brain zaps." If you’re considering stopping, work with your doctor to taper slowly over 4-6 weeks. Monitor your mood with the PHQ-9 tool weekly. If your score rises above 10, you’re at risk for relapse. For most women with moderate to severe depression, continuing treatment is safer than stopping.

Do SSRIs affect breastfeeding?

Yes, and it’s generally safe. Sertraline passes into breast milk in very low amounts - lower than most other SSRIs. The American Academy of Pediatrics considers sertraline compatible with breastfeeding. Fluoxetine passes in higher amounts and may build up in the baby’s system, so it’s less preferred if you’re nursing. Always discuss your options with your doctor, especially if your baby is premature or has health issues.