When a pharmaceutical company changes even a small part of how a drug is made - like swapping out a mixer, moving a step to a different room, or switching suppliers for an ingredient - it’s not just an internal operational decision. It’s a regulatory event. The manufacturing changes you make after a drug is approved can affect its safety, strength, purity, and effectiveness. That’s why every change, no matter how small it seems, must be tracked, assessed, and reported to regulators like the FDA. Get it wrong, and you could face a warning letter, a product recall, or even a shutdown.

Why Manufacturing Changes Matter

Think of a drug like a recipe. If you change the oven temperature, the flour brand, or the mixing time in a cake recipe, the final product might look the same - but taste different. The same goes for drugs. A change in equipment, process, or location can alter how an active ingredient behaves. Maybe it dissolves slower. Maybe impurities form. Maybe the tablet breaks too easily. These aren’t theoretical risks. In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically because companies changed manufacturing equipment without proper approval. The FDA’s goal isn’t to slow down innovation. It’s to make sure that every pill a patient takes does exactly what it’s supposed to - every time. That’s why the system is built around risk. Not all changes are created equal. Some are minor. Some are major. And the rules for each are very clear.The Three Tiers of FDA Change Reporting

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration uses a three-tier system to manage post-approval manufacturing changes. This system is laid out in 21 CFR 314.70 for drugs and 21 CFR 601.12 for biologics. Each category has strict rules about when you can make the change and how much notice you must give.- Prior Approval Supplement (PAS) - This is for major changes. If you’re changing the chemical synthesis route for your active ingredient, moving production to a new factory, or switching to a new type of sterilizer that affects critical quality parameters, you need FDA approval before you make the change. You submit a PAS, and you can’t ship the product until the FDA says yes. This can take 6 to 12 months.

- Changes Being Effected in 30 Days (CBE-30) - These are moderate changes. Examples include replacing a tablet press with an identical model from the same manufacturer, changing a filter supplier with equivalent specifications, or updating software in a control system that doesn’t alter the process outcome. You can implement the change after submitting the CBE-30, but you must wait 30 days before shipping product. If the FDA disagrees with your classification, they can stop you.

- Annual Report - Minor changes go here. Think: changing the label font size, moving a non-critical step within the same facility, or updating documentation. These don’t need pre-approval or a 30-day wait. You just document them and include them in your annual report, due within 60 days of your application’s anniversary date.

What Counts as a Major Change?

Major changes trigger a PAS. These aren’t guesses - they’re defined by impact. If a change could affect a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA), it’s major. CQAs are the measurable properties that define whether the drug works - things like dissolution rate, potency, particle size, or microbial limits. Here’s what the FDA considers major:- Changing the synthetic pathway for an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)

- Introducing a new manufacturing site for a critical step

- Switching from batch to continuous manufacturing

- Replacing a lyophilizer (freeze-dryer) with a different model that alters drying time or pressure

- Changing the source of a key excipient that affects stability

What Counts as a Moderate Change?

Moderate changes are tricky. They’re not major, but they’re not trivial either. You can implement them after submitting a CBE-30 - but you still need to prove they won’t hurt quality. Common moderate changes include:- Replacing equipment with an identical model from the same manufacturer

- Changing a supplier of a non-critical component (e.g., a gasket or seal) with equivalent material specs

- Updating a control system’s software version if it doesn’t alter process parameters

- Revalidating a process after a facility move within the same site

How Companies Classify Changes in Practice

In theory, the rules are clear. In practice, they’re messy. A senior regulatory affairs specialist on Reddit shared that classifying a tablet press replacement took 37 hours of meetings across QA, manufacturing, and validation teams. Why? Because the API’s particle size was borderline. Was the new press going to crush the particles too much? They ran tests. They compared batch data. They documented everything. Still, they had to assume the worst and file a CBE-30. Large companies like Pfizer use internal risk-scoring tools. Their system rates changes on 15 factors: impact on CQAs, validation status, historical performance, supplier reliability, and more. A score above 80? That’s a PAS. Below 30? Annual report. In between? CBE-30. Smaller companies don’t have those tools. Many rely on templates from trade groups like the Parenteral Drug Association (PDA). But even those can be overwhelming. ASQ data shows regulatory staff need 18 months of training to consistently classify changes correctly.Global Differences in Requirements

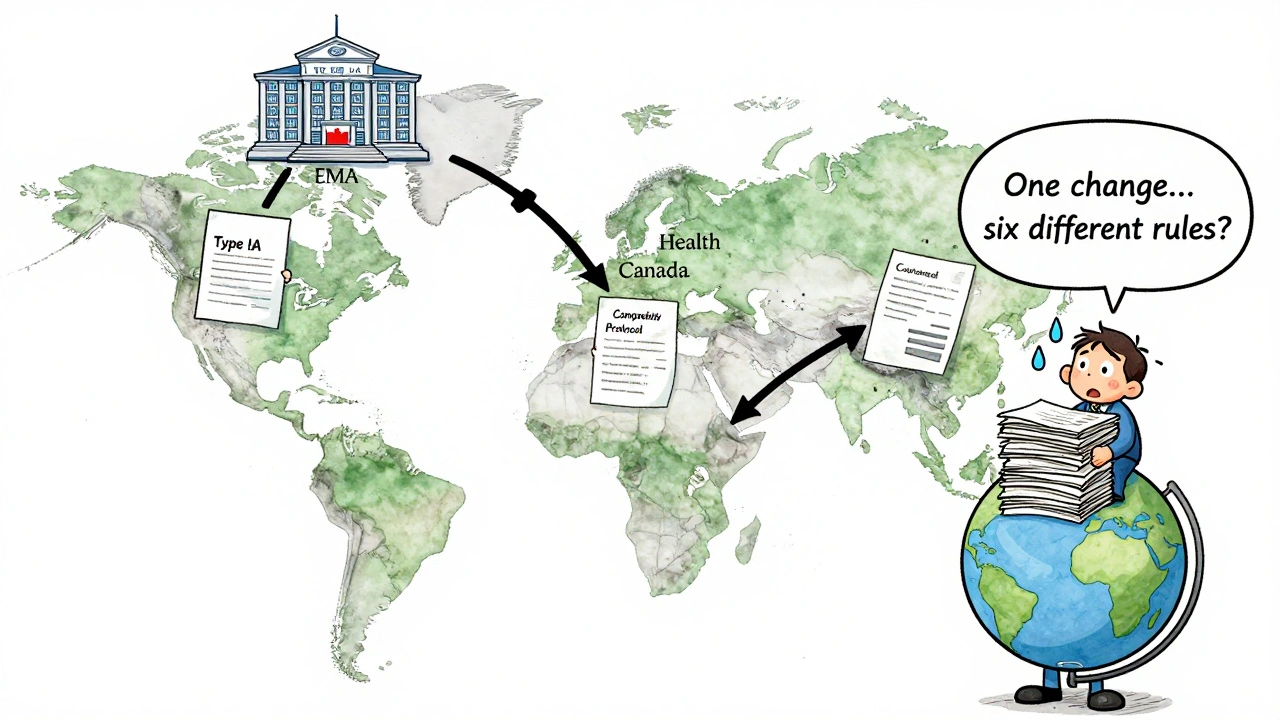

The U.S. isn’t the only player. Europe, Canada, and the WHO have their own rules - and they don’t always match.- EMA (Europe): Uses Type IA (minor, notify within 12 months), Type IB (moderate, approve before implementation), and Type II (major, full review). No 30-day waiting period - you must wait for approval. But they offer accelerated review for some Type IB changes.

- Health Canada: Level I = PAS, Level II = notify and wait, Level III = annual report. Similar to FDA, but with different timelines.

- WHO: Requires a Comparability Protocol - a full study showing the old and new versions are the same. This is common for vaccines and biologics.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

In 2022, 22% of all FDA warning letters were tied to manufacturing change violations. Of those, 37% were about equipment changes - the most common mistake. Why? Because companies assume “equivalent” means “same.” It doesn’t. A new pump might look identical, but if it has a different impeller design, it could create more shear force - and damage your drug’s structure. One company replaced a filter with a cheaper version. The new filter had a slightly different pore size. It caught fewer particles. The product failed stability testing six months later. The FDA shut down the line. The recall cost over $12 million. There’s also the hidden cost: time. A single CBE-30 submission can take 120 hours of work across teams. A PAS? That’s 400+ hours. For small companies, that’s a quarter of their regulatory budget.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The system isn’t static. The FDA released a draft guidance in 2023 on using ICH Q9 risk management principles to streamline change classification. That means companies will be encouraged to use tools like Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to justify their decisions - not just check boxes. Also, continuous manufacturing is growing. In 2022, the FDA said that equipment changes in continuous systems almost always require a PAS because everything is connected. A change in one unit affects the whole line. By 2025, experts predict 40% of change submissions will include real-time quality data - from sensors monitoring temperature, pressure, or particle size during production. This data could help prove a change had no effect, reducing the need for lengthy stability studies.How to Avoid Common Mistakes

Here’s what actually works in the real world:- Don’t guess the category. If you’re unsure, ask the FDA. Early consultation is built into their guidance. It’s not a sign of weakness - it’s smart risk management.

- Document everything. You need facility diagrams, validation reports, and at least three consecutive batch comparisons. If you can’t show it, you didn’t do it.

- Test before you change. Run a small-scale trial. Compare the old and new versions side-by-side. Measure CQAs. Use statistics. Don’t rely on “it looks fine.”

- Train your team. Regulatory staff need ongoing training. One 2-hour seminar a year isn’t enough. Make it part of your quality culture.

- Use a change control system. Even small companies can use low-cost software to track submissions, deadlines, and approvals. Spreadsheets break. Systems don’t.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Compliance - It’s About Trust

Regulators don’t want to be your enemy. They want to make sure your medicine works. Every time you submit a change request, you’re not just checking a box - you’re asking them to trust you. If you cut corners, they’ll lose that trust. And once it’s gone, it’s hard to get back. The best manufacturers don’t just follow the rules. They anticipate them. They test before they change. They document before they ask. And they know that in pharmaceutical manufacturing, the smallest change can have the biggest impact.What happens if I make a manufacturing change without notifying the FDA?

If you make a change without proper notification - especially a major one requiring a PAS - the FDA can issue a warning letter, order a product recall, or halt distribution. In 2023, four companies received warning letters specifically for unapproved equipment changes. The FDA considers this a serious violation because it puts patient safety at risk. Even if the change seems harmless, you’re bypassing the system designed to catch hidden quality issues.

Can I use a CBE-30 for any equipment replacement?

No. A CBE-30 is only allowed if the new equipment is truly equivalent - same principle of operation, same critical dimensions, same material of construction. If you’re upgrading to a more advanced machine, even if it’s faster or more efficient, you likely need a PAS. The FDA’s 2022 guidance clarifies that “equivalent” doesn’t mean “better.” It means functionally identical in how it affects your product’s quality.

Do I need to revalidate my entire process after a minor change?

Not always. For minor changes reported annually, you typically only need to validate the specific part that changed - not the whole process. For example, if you change a label supplier, you don’t need to revalidate the tablet press. But you must still demonstrate that the change didn’t affect product quality. That means testing at least three batches for critical attributes like potency, dissolution, and appearance.

How long does a PAS take to get approved?

A Prior Approval Supplement typically takes 6 to 12 months for the FDA to review. Complex changes - like switching to continuous manufacturing or moving production overseas - can take longer. The clock starts when the FDA receives your submission. You cannot ship the changed product until you get written approval. Many companies start preparing PAS submissions 12 to 18 months in advance to avoid production delays.

Is there a way to speed up the approval process for moderate changes?

In the U.S., the CBE-30 process is already the fastest path for moderate changes - you can ship after 30 days if the FDA doesn’t respond. In Europe, the EMA introduced an “accelerated Type IB” pathway in 2023 that cuts review time from 60 to 30 days for certain equipment changes. The FDA has not adopted a similar system yet, but its 2023 draft guidance on risk-based approaches suggests future flexibility may be coming.

All Comments

Audrey Crothers December 12, 2025

This is so true! I worked at a small pharma shop last year and we changed a mixer supplier thinking it was 'equivalent' - turns out the impeller angle was off by 2 degrees. Our batch failed dissolution. We had to scrap $200k worth of product. 😭 Never assume. Always test.

Stacy Foster December 12, 2025

Of course the FDA is cracking down - they’re just protecting Big Pharma’s profits. Why do you think they make you wait 12 months for a PAS? So the big guys can keep their monopolies. Small companies get crushed. This isn’t safety - it’s control. #PharmaCartel

Donna Anderson December 14, 2025

Yesss!! I love how this breaks it down so simply. I used to think 'minor change' meant 'who cares' - now I know it’s like changing the sugar in your grandma’s cookie recipe. Even a pinch can mess it up. 🙌 Thanks for the clarity!

Levi Cooper December 15, 2025

Europe’s system is just lazy. Why wait for approval? In America, we move fast and break things - and that’s why we lead in innovation. If you can’t keep up, maybe you shouldn’t be making medicine.

sandeep sanigarapu December 17, 2025

Clear and precise. The three-tier system is logical. In India, we often lack resources to validate every change. But this framework helps prioritize. Thank you for sharing.

Nathan Fatal December 17, 2025

What’s interesting is how this mirrors the philosophy of trust in science. The system isn’t about control - it’s about epistemic responsibility. We don’t just make pills; we make promises to people who are sick. Every change is a covenant. If we treat it like a spreadsheet task, we’ve already lost.

nikki yamashita December 17, 2025

Love this! I’m a QA newb and this made me feel less scared. We’re not the enemy - we’re the guardians. 💪

Adam Everitt December 18, 2025

Interesting… though I wonder if the FDA’s framework is… *sigh*… just a bit too rigid? I mean, we’re talking about *pills*. Not nuclear reactors. But I suppose, yeah, better safe than… you know…

wendy b December 20, 2025

Actually, the terminology is incorrect. It's not 'CBE-30' - it's 'Changes Being Effected Within 30 Days'. And 'PAS' is 'Prior Approval Supplement'. If you're going to write about regulation, at least get the acronyms right. Amateur hour.

Rob Purvis December 20, 2025

Can we talk about how the real problem is training? I’ve seen QA teams with 3 people handling 80+ change requests a month. No one has time to think. They just check boxes. And that’s why mistakes happen. We need more people, better tools, and less pressure. This isn’t a compliance problem - it’s a systemic one.

Laura Weemering December 20, 2025

I just… I can’t. Every time I read about another $12M recall… I feel like we’re all just running on a hamster wheel. Who’s really benefiting? The regulators? The lawyers? The consultants? Not the patients. Not the workers. Just… the system. And it’s exhausting.

Reshma Sinha December 22, 2025

Global harmonization is the key. EMA, FDA, WHO - we need a unified framework. Otherwise, the cost of compliance is killing innovation in emerging markets. We need risk-based, not paperwork-based, systems.

Lawrence Armstrong December 22, 2025

Just had a team member ask if we could skip the CBE-30 because the new pump "looks the same." I sent them this post. 🤝👍