When you pick up a prescription, you might not think about why one pill costs $5 and another costs $50-even if they do the exact same thing. The difference isn’t in effectiveness. It’s in cost-effectiveness analysis. This isn’t just a fancy term used by economists. It’s the quiet system that decides which drugs get covered by insurance, which ones pharmacies stock, and ultimately, which ones you can afford.

Generic drugs aren’t cheap because they’re low quality. They’re cheap because they don’t need to pay for research, marketing, or patent protection. But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal. Some cost 10 times more than others that work just as well. And if you’re a health plan, hospital, or even a patient paying out of pocket, that difference adds up fast.

Why Generics Aren’t Always the Cheapest Option

It sounds simple: brand-name drug expires → generic comes out → price drops. But reality is messier. When the first generic hits the market, prices usually fall by about 40%. With six or more competitors, prices drop over 95% below the original brand. That’s what the FDA found. But here’s where things get strange: even among generics, prices vary wildly.

A 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at the top 1,000 generic drugs in use. They found 45 of them were being sold at prices 15.6 times higher than other drugs in the same therapeutic class. One example: a generic version of a blood pressure drug might cost $120 a month, while another generic that works identically costs just $8. The active ingredient is the same. The FDA says they’re equivalent. So why the gap?

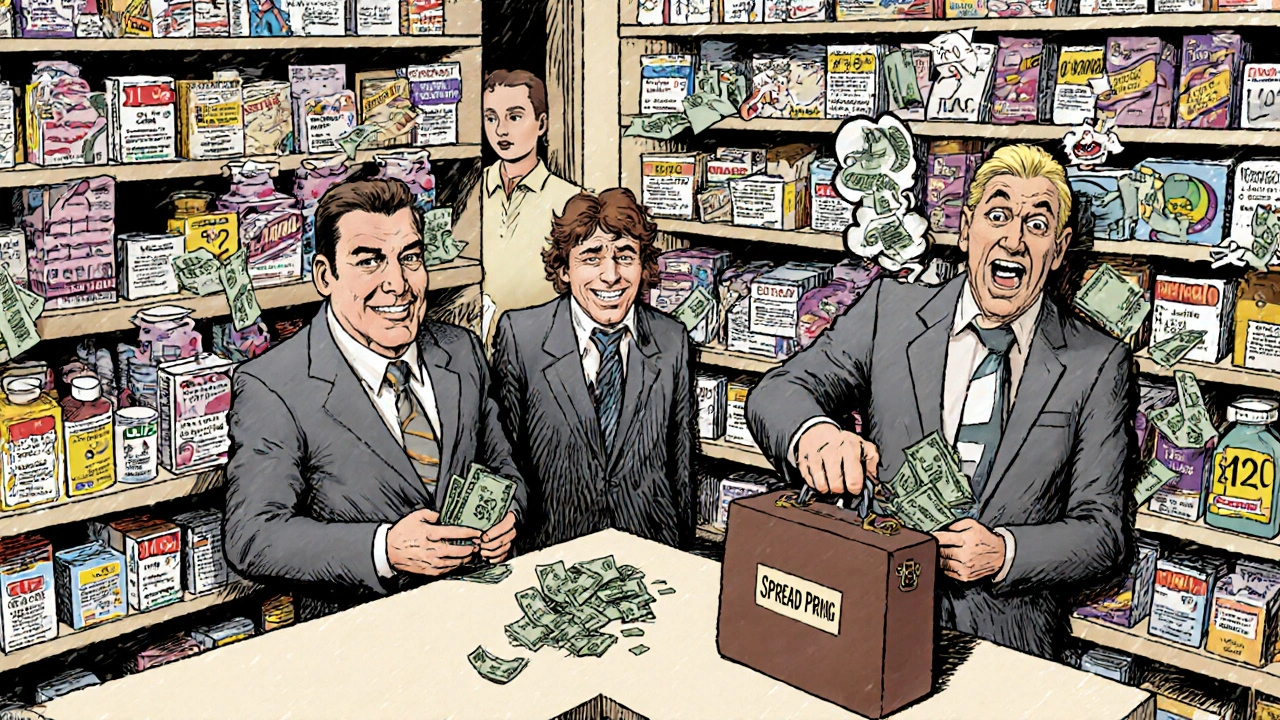

It’s not about quality. It’s about market distortion. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies-often profit from what’s called “spread pricing.” They negotiate a lower price with the pharmacy but charge the insurer a higher price. The difference? Their cut. So if a high-cost generic pays them more, they’ll keep it on the formulary-even when a cheaper, equally effective option exists.

How Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Works

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) measures value-not just price. It asks: How much health do we get for every dollar spent? The standard metric is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, or ICER. That’s the extra cost divided by the extra health benefit, usually measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

For generics, that means comparing:

- Cost of Drug A (generic)

- Cost of Drug B (cheaper generic or therapeutic alternative)

- Health outcomes from each

If Drug A costs $100 more per year but gives the same results as Drug B, then Drug B wins. Simple. But here’s the problem: most studies don’t look ahead. A 2021 ISPOR report found that 94% of published CEAs ignore future generic entry. That’s like betting on a stock price without checking when the company’s patent expires.

Real-world CEA needs to account for timing. If a drug’s patent expires in 18 months, a cost analysis done today that assumes it’ll stay expensive is misleading. It makes generics look less valuable than they’ll actually be. That’s why experts like Dr. John Garrison warn that failing to model patent cliffs creates “pricing anomalies” that hurt innovation and distort coverage decisions.

The Hidden Savings in Therapeutic Substitution

Therapeutic substitution means switching from one drug to another in the same class-not just a different brand of the same drug. For example, swapping one statin for another, or one antidepressant for another with similar effectiveness.

The JAMA study showed that when patients were switched from high-cost generics to lower-cost therapeutic alternatives, total spending dropped from $7.5 million to just $873,711. That’s an 88% savings. And no one got sicker. No side effects increased. Just smarter choices.

But here’s what’s surprising: the biggest price gaps weren’t between brand and generic. They were between two generics. One generic of a drug might cost 20 times more than another generic in the same class. Why? Because of dosage form. A tablet might be $5. A capsule with a delayed-release coating? $100. But if the clinical effect is the same, is the coating worth 20x the cost? Usually, no.

Even identical drugs from different manufacturers vary in price. On average, one generic costs just 1.4 times more than another. That’s a small spread. But when you’re talking about millions of prescriptions, that 40% markup adds up to hundreds of millions in wasted spending.

Who’s Doing It Right-and Who’s Not

In Europe, over 90% of health technology assessment agencies use formal CEA to decide which drugs to cover. In the U.S., only 35% of commercial insurers do. Why the gap?

It’s partly culture. U.S. payers often rely on formularies built by PBMs, not economists. It’s also partly legal. Medicare Part D, for example, is legally barred from negotiating drug prices directly. That means they can’t push for lower-cost generics the way the VA can.

The VA, on the other hand, has been a leader. They use their own pricing data-Federal Supply Schedule and VA-specific rates-to calculate true costs. Their numbers show that generics cost only 27% of the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), while brand drugs cost 64%. That’s a huge difference. And they adjust for it. That’s why the VA spends far less per prescription than private insurers.

Meanwhile, drug companies know this. They set prices just below the cost-effectiveness threshold that payers use. If a payer says, “We’ll pay up to $100,000 per QALY,” the manufacturer sets the price so the ICER is $98,000. It’s not manipulation-it’s math. But it only works if the analysis is done right.

What Needs to Change

Three things are missing from most CEA models today:

- Future generic entry - Analysts need to forecast when generics will hit the market, not assume prices stay high.

- Therapeutic alternatives - Don’t just compare one generic to a brand. Compare all generics and similar drugs in the class.

- PBM spread pricing - If you’re measuring cost to the system, you need to account for hidden profits that inflate prices.

The NIH’s 2023 framework gives a roadmap: design proportionate processes, assess multiple options, and update decision rules as new generics appear. That’s not just smart economics. It’s ethical.

Consider this: in 2017 alone, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. That’s more than the GDP of Norway. And yet, we’re still overpaying for some generics because no one’s looking closely enough.

What You Can Do

If you’re a patient: ask your pharmacist. “Is there a cheaper version of this that works the same?” You’d be surprised how often the answer is yes.

If you’re an employer or insurer: demand transparency. Ask your PBM: “Why is this generic priced this way? What’s the lowest-cost therapeutic alternative?”

If you’re a clinician: don’t default to the first generic on the formulary. Check if a different one-same active ingredient, same indication-is cheaper. Use tools like GoodRx or the VA’s formulary database as references.

Cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about cutting waste. It’s about making sure every dollar spent on medicine delivers the most health possible. And with over 300 drugs losing patent protection between 2020 and 2025, getting this right has never been more important.

Generics aren’t the enemy of innovation. They’re the reward for it. But only if we pay for value-not just brand names.

Are generic drugs as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict standards for quality, purity, and performance. Bioequivalence studies prove they work the same way in the body. The only differences are in inactive ingredients like fillers or dyes-which don’t affect how the drug works.

Why do some generics cost so much more than others?

Price differences among generics aren’t due to quality-they’re due to market structure. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) often profit from the gap between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge insurers. This “spread pricing” incentivizes them to keep higher-priced generics on formularies, even when cheaper, equally effective options exist. Formulation differences (like extended-release capsules) can also justify small price increases, but not 10x or 20x gaps.

What is therapeutic substitution, and is it safe?

Therapeutic substitution means switching from one drug to another in the same class-for example, from one statin to another, or one SSRI to another. It’s safe when done under clinical guidance. Studies show that patients often respond similarly across drugs in the same class. The JAMA 2022 study found that switching from high-cost generics to lower-cost therapeutic alternatives saved 88% in spending without reducing effectiveness. Always consult your doctor before switching, but don’t assume the most expensive option is best.

Does cost-effectiveness analysis hurt innovation?

No-when done right, it supports innovation. Conventional cost-effectiveness models that ignore future generic entry actually hurt innovation by making new drugs look less valuable than they are. Experts like Dr. John Garrison argue that CEA should account for patent expiration timing. When manufacturers know their drug will face generic competition soon, they’re incentivized to innovate faster and price more responsibly. Proper CEA ensures that breakthrough drugs get fair reimbursement while preventing overpayment for older, off-patent options.

How can I find the cheapest generic for my prescription?

Use tools like GoodRx, SingleCare, or the VA’s formulary database. Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a lower-cost generic or therapeutic alternative?” Sometimes, a different manufacturer’s version or a different dosage form (like a tablet instead of a capsule) costs far less. Don’t assume the first option your insurance covers is the cheapest. Many pharmacies offer cash prices lower than insurance copays for generics.

Why don’t all insurers use cost-effectiveness analysis?

Many U.S. commercial insurers rely on Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to manage formularies, and PBMs often prioritize revenue over cost-effectiveness. Spread pricing creates a conflict of interest-higher-priced generics can mean bigger profits for PBMs. Also, CEA requires expertise in health economics, patent law, and market forecasting, which many insurers lack. Medicare Part D is legally restricted from negotiating prices, limiting its ability to use CEA effectively. In contrast, European health systems and the VA use CEA routinely because they have centralized decision-making and clearer incentives to reduce spending.

All Comments

Katy Bell November 22, 2025

I used to think generics were all the same until my pharmacist handed me a $7 version of my blood pressure med instead of the $120 one my insurance pushed. I asked why and she just shrugged and said, 'PBMs make bank on the markup.' I’ve been using GoodRx ever since. Mind blown. 😅

Ragini Sharma November 23, 2025

so like… generics cost 10x more just bc someone in a suit got a cut?? 😭 i mean i get it but also… why is this even a thing?? india makes generics for pennies and we’re paying like 200$ for the same pill?? smh

Linda Rosie November 25, 2025

The data is clear. Cost-effectiveness analysis, when properly applied, reduces waste without compromising outcomes. The issue lies in structural incentives, not clinical value.

Vivian C Martinez November 26, 2025

Hey, if you’re on a tight budget, always ask your pharmacist for alternatives. Seriously. I switched from a $90 generic to a $4 one last year-same effect, zero side effects. Small change, huge relief. You’ve got this 💪

Ross Ruprecht November 27, 2025

Ugh I’m so tired of this. Why do we even have to think about this stuff? Just give me my pills and shut up.

Bryson Carroll November 27, 2025

Everyone’s acting like this is some deep secret but it’s just capitalism 101. PBMs are parasites. Doctors are complicit. Patients are suckers. The system is designed to extract, not heal. And you think a $8 pill is ‘equivalent’? Sure. Until you’re the one paying for the side effects from the cheap filler that got swapped in. Good luck.

Dalton Adams November 27, 2025

Y’all don’t get it. The FDA doesn’t test fillers. So yeah, two generics can be ‘bioequivalent’ but one has cornstarch that gives me hives. The other has lactose. I’ve been hospitalized over this. So don’t just say ‘same drug.’ It’s not the same for me. 🤷♂️

Kane Ren November 29, 2025

Look, I know it sounds crazy, but if you’re on a chronic med, check your local pharmacy’s cash price. Sometimes it’s cheaper than your insurance copay. I saved $400 last year just by asking. It’s not hard. Just do it.

Charmaine Barcelon November 30, 2025

STOP. STOP. STOP. You people are so naive. You think it’s about money? No. It’s about control. The system wants you dependent. It wants you confused. It wants you to keep buying the expensive stuff because you don’t know better. And now you’re just… accepting it?!

Karla Morales November 30, 2025

It’s not just PBMs. It’s also the manufacturers who intentionally delay generic entry by filing frivolous patents. 🤦♀️ And then they wonder why healthcare costs are insane. This is systemic corruption dressed up as ‘market dynamics.’

Javier Rain November 30, 2025

Let me tell you something-this is why I became a pharmacist. People think we just hand out pills. No. We’re the ones fighting the system so you don’t get ripped off. I spend 20 minutes a day helping patients find cheaper options. It’s exhausting. But worth it. Keep asking. Keep pushing.

Laurie Sala December 2, 2025

And yet… you still trust the system? After all this? You still believe the FDA? The VA? The ‘equivalent’ labels? I’ve seen people die because they were switched to a ‘cheaper’ version and it triggered a reaction no one predicted. This isn’t economics. This is a gamble with lives.

Lisa Detanna December 2, 2025

In my home country, we don’t have this mess. Generics are priced by the government. No PBMs. No spread pricing. Everyone gets the same low price. It works. We don’t have to Google ‘best generic for X’-we just get it. Maybe we’re not perfect, but at least we don’t treat medicine like a casino.

Demi-Louise Brown December 4, 2025

Therapeutic substitution is clinically sound and cost-efficient. Evidence supports its use. Implementation requires clinician education and system alignment.

Matthew Mahar December 4, 2025

wait so if i just ask my doc for a different brand of the same pill i can save like 90%?? why has no one told me this before?? i’ve been paying $150 for 3 years 😭