When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see two pills that look completely different-one with a brand name, another labeled as generic. You might wonder: Are they really the same? The answer lies in a term you’ve probably never heard before: bioequivalent.

What bioequivalence actually means

Bioequivalence isn’t about two drugs looking the same or having the same inactive ingredients. It’s not even about being chemically identical. It’s about what happens inside your body after you take them. If two medications are bioequivalent, they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at roughly the same speed. That’s it. No more, no less.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in how quickly and how much of the drug gets absorbed. For most drugs, that means the generic version must release the same amount of medicine into your blood as the brand-name version, within a range of 80% to 125%. That might sound loose, but it’s not. Decades of data show that a difference this small doesn’t change how well the drug works-or how safe it is-for most people.

Think of it like two cars driving the same route. One is a new model, the other is an older version. They don’t have to be identical in color or radio, but if they both get you from point A to point B using the same amount of gas and taking the same amount of time, they’re effectively equivalent. That’s bioequivalence.

How bioequivalence is tested

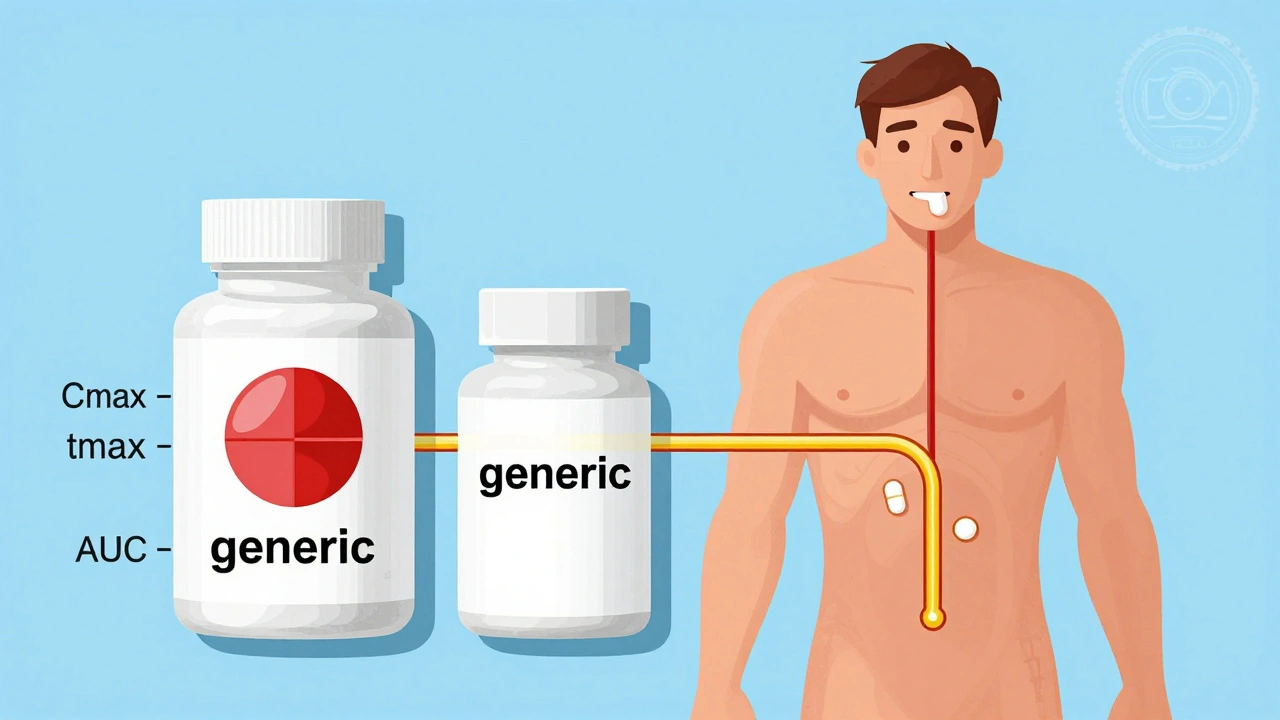

To prove two drugs are bioequivalent, manufacturers run studies with healthy volunteers-usually between 24 and 36 people. These participants take one version of the drug, then after a waiting period, take the other. Blood samples are drawn over several hours to track how much of the drug is in the bloodstream and how fast it gets there.Three key numbers are measured:

- Cmax-the highest concentration of the drug in the blood

- tmax-how long it takes to reach that peak

- AUC-the total amount of drug absorbed over time

For the drugs to be approved as bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for these numbers must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s values. This range isn’t pulled out of thin air. It’s based on statistical analysis of real-world outcomes. A 20% difference in absorption is considered too small to cause a meaningful change in how the drug works for most conditions.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where the difference between a helpful dose and a dangerous one is tiny-the rules tighten. For example, with drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain epilepsy medications, the acceptable range shrinks to 90% to 111%. The FDA requires extra scrutiny for these because even small changes can matter.

Bioequivalent vs. pharmaceutical equivalent vs. therapeutic equivalent

It’s easy to mix up these terms, but they’re not the same:- Pharmaceutical equivalent means two drugs have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They might differ in color, shape, or filler ingredients, but the key medicine is identical.

- Bioequivalent means they perform the same way in the body-same absorption rate and amount.

- Therapeutic equivalent means they’re both pharmaceutical and bioequivalent. Only then does the FDA give them an ‘AB’ rating, meaning they can be swapped without concern.

The FDA publishes all this in the Orange Book, a public list of approved drugs and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. If a generic drug has an ‘AB’ rating, you can be confident it’s a direct substitute. If it’s ‘BX’, it’s not considered interchangeable.

Why bioequivalence matters

Generic drugs make up about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. That’s not because they’re cheaper to make-it’s because they’re cheaper to buy. The average generic saves patients $313 per prescription compared to the brand name. Over the past decade, generics have saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $2.2 trillion.Without bioequivalence standards, there’d be no way to guarantee those savings wouldn’t come at the cost of safety or effectiveness. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created this system to balance innovation with affordability. It lets generic companies skip expensive clinical trials-because they’re proving equivalence, not inventing something new.

But here’s the catch: not all drugs are created equal. For most medications-antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants-bioequivalence works perfectly. But for a small group of drugs, especially those with narrow therapeutic windows, some patients report differences after switching. A 2021 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 0.8% of epilepsy patients had breakthrough seizures after switching from brand to generic. That’s a tiny number, but it’s real.

Pharmacists often hear these stories. In fact, many states require pharmacies to stick with the same generic manufacturer once a patient starts on one. Why? Because even if two generics are both bioequivalent to the brand, they might not be bioequivalent to each other. The inactive ingredients, coating, or manufacturing process can subtly affect how the drug is released.

What patients really experience

Consumer Reports surveyed over 3,400 people in 2023. Of those taking generics, 78% were satisfied. Brand-name users reported 82% satisfaction. The biggest gap? With epilepsy drugs. Nearly 12% of patients on generic antiepileptics reported issues-compared to just 2% on brand-name versions.On Reddit, pharmacists and patients share stories. One user wrote: “I’ve been on levothyroxine for 10 years. Switched generics last year. My TSH shot up. Went back to the original brand-back to normal.” Another said: “My cholesterol med switched to generic. No change at all. Saved me $200 a month.”

The FDA’s own adverse event database shows that reports of problems with generic drugs are proportional to their market share. Only 0.3% of all medication reports involve generics-even though they’re used 90% of the time. That suggests the system works as intended.

What’s changing now

The FDA is updating its approach for complex drugs-things like inhalers, nasal sprays, and topical creams. These don’t get absorbed into the bloodstream the same way pills do. For them, bioequivalence might be proven through skin absorption tests, lung deposition studies, or even clinical outcomes instead of blood levels.Since 2020, the FDA has released 27 new guidance documents to help manufacturers navigate these tricky cases. And in 2023, they launched a $25 million research program to develop better methods for testing complex generics.

Some experts are pushing for personalized bioequivalence. Instead of one-size-fits-all 80-125% rules, they want models that account for how different people metabolize drugs. But that’s still theoretical. For now, the FDA stands by the current system: “It’s worked for decades,” says Commissioner Robert Califf. “And it continues to deliver safe, affordable medicines.”

What you should do

If you’re on a generic drug and feel fine-stick with it. You’re saving money without sacrificing effectiveness. If you’re switching from brand to generic and notice something off-changes in energy, mood, side effects, or how well your condition is controlled-talk to your doctor. Don’t assume it’s “all in your head.”For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like thyroid meds, seizure drugs, blood thinners, or certain heart medications-ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same manufacturer as before?” If you’ve had a good response to one generic, ask them to keep filling it the same way.

And remember: just because two generics are both approved doesn’t mean they’re interchangeable with each other. That’s why pharmacists track which one you’re on. It’s not about brand loyalty-it’s about consistency.

At the end of the day, bioequivalence isn’t magic. It’s science. It’s data. It’s a system designed to make healthcare affordable without compromising care. And for the vast majority of people, it works.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs must meet the same strict quality, safety, and effectiveness standards as brand-name drugs. The FDA requires them to contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and be manufactured under the same rules. The only differences are in inactive ingredients like color or filler, which don’t affect how the drug works.

Why do generic drugs look different from brand-name ones?

By law, generic drugs can’t look exactly like the brand-name version. That’s to avoid confusion and trademark issues. So they might be a different color, shape, or size. But the active ingredient-and how your body absorbs it-must be the same. The differences are purely cosmetic.

Can I switch between different generic versions of the same drug?

For most drugs, yes. But for medications with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or seizure drugs-it’s better to stick with the same generic manufacturer. Even though both generics are approved as bioequivalent to the brand, they may not be bioequivalent to each other. Small differences in how the drug is released can matter.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

A small number of patients report differences, especially with drugs where the margin between effective and toxic doses is very narrow. Studies show these cases are rare-less than 1% for most drugs. But when they happen, it’s often because the patient switched between different generic manufacturers, not because the generic is inferior. Consistency in the manufacturer can help avoid these issues.

How does the FDA decide if a generic is bioequivalent?

The FDA requires human studies showing that the generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream as the brand-name drug, within a 80% to 125% range. For high-risk drugs, the range is tighter-90% to 111%. These studies involve healthy volunteers and measure blood levels over time. The data is reviewed by FDA scientists before approval.

Are all generic drugs approved the same way?

No. Most are approved using standard bioequivalence studies. But for complex products-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-the FDA allows alternative methods. These might include in vitro testing, clinical endpoint studies, or pharmacodynamic measurements. The approach depends on how the drug is absorbed and how it works in the body.

All Comments

John Fred December 13, 2025

Bioequivalence is wild when you think about it 🤯 Two pills that look nothing alike but do the exact same job inside your body? Science is cool. The 80-125% range? Totally fine for 99% of meds. I’ve been on generics for years - no issues, saved thousands. 💸💊

Jamie Clark December 14, 2025

You call that science? It’s corporate math dressed up in lab coats. 80-125%? That’s a 45% swing. You’d never accept that kind of variance in a jet engine or a pacemaker. But pills? Oh, sure, throw ‘em in the blender and call it ‘equivalent.’ The FDA’s been captured by Big Pharma’s generic subsidiaries. Wake up.

Tommy Watson December 16, 2025

bro i switched my zoloft to generic and i felt like a zombie for 3 weeks 😭 like i was underwater. my doc said ‘it’s the same chem’ but no it wasn’t. i went back to brand and boom - i was me again. why do they even let this happen? 😤

Donna Hammond December 16, 2025

Tommy, your experience isn’t rare - and it’s valid. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows like SSRIs, even tiny differences in release profiles can cause real symptoms. That’s why pharmacists track the manufacturer. It’s not about brand loyalty - it’s about consistency. If you found a generic that works, stick with it. And if you switch? Tell your provider. Your body’s feedback matters.

Willie Onst December 17, 2025

Love how this post breaks it down. Bioequivalence is like two different chefs making the same dish - one uses organic garlic, the other uses store-bought. Taste? Almost identical. But if you’re super sensitive to garlic? You’ll notice. That’s why we need to respect the 0.8% who have real reactions. It’s not anti-generic - it’s pro-patient.

Ronan Lansbury December 19, 2025

Let’s be real - the FDA doesn’t test generics on real patients. They test on healthy volunteers who don’t have chronic conditions. That’s a massive flaw. And the 80-125% range? It’s designed so manufacturers can cut corners. I’ve seen the documents. This isn’t science - it’s regulatory theater.

Shelby Ume December 19, 2025

For those of you worried about switching: if you’re on a thyroid med, seizure drug, or blood thinner - don’t switch manufacturers without talking to your pharmacist. Even if both are ‘AB’ rated, the coating or filler can change absorption. I’ve seen patients crash because they got a different generic. Consistency > cost savings. Always.

Jade Hovet December 19, 2025

OMG YES!! I switched my BP med to generic and my head exploded 😵💫 Like, I was dizzy for 2 weeks. Went back to brand - instant relief. My pharmacist said ‘they’re the same’ but my body said NOPE. So now I pay extra and I’m fine. My health > my wallet. 💖💊 #GenericFail

nithin Kuntumadugu December 20, 2025

lol u think this is science? they test on 24 people for 7 days and call it a day. what about elderly? what about people with liver disease? what about 1000+ other variables? this whole system is rigged. big pharma owns the FDA. u r being played. 😏

Harriet Wollaston December 21, 2025

I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years. I’ve seen people panic over generics - then realize they feel better because they’re finally taking their meds (they’re cheaper!). But I’ve also seen people who had breakthrough seizures after switching generics. We don’t judge. We track. We ask: ‘Which one did you take last?’ That’s the real magic. Not the label. The record.

Lauren Scrima December 21, 2025

Wow. So you’re telling me… the system works… for most people…? Shocking. 😏 Next you’ll say water is wet. At least the FDA admits the 80-125% range is arbitrary. But hey, at least it’s cheaper than paying $1,200 for a month’s supply of lisinopril. I’ll take my savings and my slightly less predictable absorption, thanks.

sharon soila December 22, 2025

Every human deserves access to life-saving medication. Bioequivalence isn’t perfect - but it’s the best system we have to make that possible. For the 99%, it’s safe. For the 1%, we listen. And we improve. That’s how progress works - not by tearing down systems, but by refining them with data, empathy, and patience.

nina nakamura December 22, 2025

80-125% is a joke. That’s not equivalence. That’s a gamble. And you people act like it’s gospel. You think your thyroid meds are safe? You think your seizures won’t return? Wake up. The data is cherry-picked. The studies are short. The patients are young and healthy. You’re being used as lab rats. And you’re thanking them for the discount.

Rawlson King December 24, 2025

Don’t be naive. The FDA approves generics based on lab results from manufacturers who pay for the tests. That’s a conflict of interest. And you think that’s acceptable? You’re not saving money - you’re funding a system that puts profits before precision. This isn’t healthcare. It’s commodified medicine.