When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure that’s true? The answer lies in bioequivalence studies - the science-backed process every generic drug maker must pass before their product hits the shelf.

Why Bioequivalence Matters

Generic drugs save patients and the healthcare system billions each year. In the U.S., they make up 90% of all prescriptions but cost only 23% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s a huge win - but only if those generics are just as safe and effective. That’s where bioequivalence comes in.The FDA doesn’t just accept a generic drug because it looks the same or has the same active ingredient. It demands proof that the body absorbs and uses the drug in exactly the same way. This isn’t about chemistry on paper - it’s about what happens inside your bloodstream after you swallow the pill.

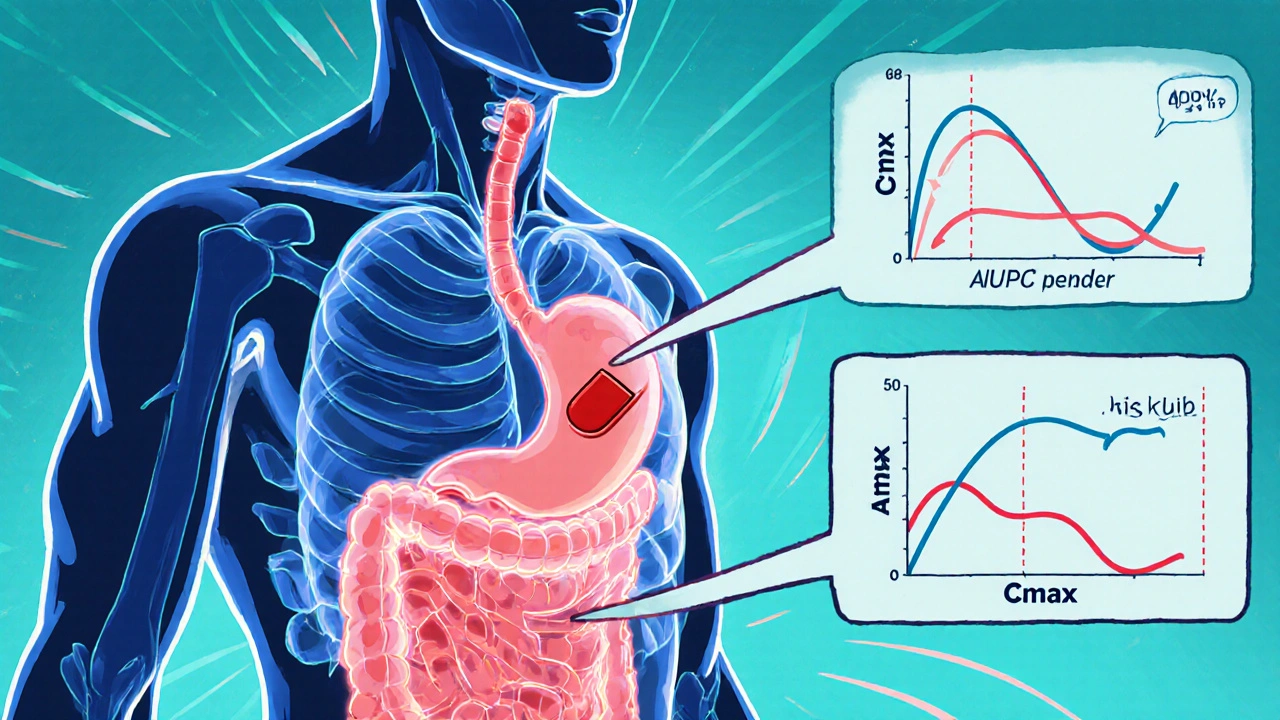

The Core Requirements: AUC and Cmax

To prove bioequivalence, manufacturers run clinical studies in healthy volunteers. These studies track how the drug moves through the body over time. Two key measurements are used:- AUC (Area Under the Curve) - This shows how much of the drug enters your system overall. Think of it as the total exposure.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration) - This tells you how quickly the drug reaches its highest level in your blood. It’s about how fast the effect kicks in.

The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values - between the generic and the brand-name drug (called the Reference Listed Drug or RLD) - must fall between 80% and 125%. This is known as the 80/125 rule. It’s not arbitrary. Decades of research show that if two drugs meet this standard, they’ll produce the same therapeutic effect in most patients.

These studies are done under strict conditions: usually in 24 to 36 healthy adults, after an overnight fast. For drugs that are affected by food, a second study is done after eating. The data must come from labs using validated, accurate methods - no shortcuts allowed.

What If the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Not all drugs behave the same way in the body. Some, like warfarin or levothyroxine, have very narrow therapeutic windows. A tiny difference in absorption could mean the difference between treatment and danger.For these narrow therapeutic index drugs (NTIDs), the FDA tightens the rules. Instead of 80-125%, the acceptable range is 90-111%. That’s a much narrower margin, and it’s why generic versions of these drugs take longer to approve and require more data.

Other drugs, like some antidepressants or blood pressure meds, show high variability in how people absorb them. For these, the FDA allows something called scaled average bioequivalence (SABE). This method adjusts the acceptance range based on how much the drug varies from person to person. It’s a smarter, more flexible approach - but only for specific cases approved by the FDA.

When Can You Skip the Human Study? (Biowaivers)

Not every generic needs a full clinical trial. The FDA allows biowaivers - exceptions where in vitro (lab-based) testing replaces human studies.These are granted under strict conditions, often using the Q1-Q2-Q3 framework:

- Q1: Same active ingredient and inactive ingredients (fillers, binders, etc.)

- Q2: Same dosage form and strength

- Q3: Same physical and chemical properties - like pH, dissolution rate, and particle size

Biowaivers are common for:

- Oral solutions (like liquid antibiotics)

- Topical creams or gels meant to work on the skin, not in the bloodstream

- Ophthalmic and otic drops

For topical products, the FDA may accept in vitro release testing (IVRT) or in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) instead of measuring blood levels. This saves time and money - and speeds up access to affordable medicines.

What Goes Into a Successful Submission?

Submitting an ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) isn’t just about running a study. It’s about documenting everything perfectly.Many applications get rejected on the first try. In 2022, only 43% of ANDAs got approved in the first review cycle. Why? Common mistakes include:

- Too few volunteers

- Poorly designed study protocols

- Inaccurate lab methods for measuring drug levels

- Missing or disorganized documentation

Companies that follow the FDA’s Product-Specific Guidances (PSGs) have a much better shot. There are over 2,100 of these guides - each one details exactly what’s needed for a specific drug. Following them boosts first-cycle approval rates from 29% to 68%.

And it’s not just about paperwork. The FDA expects studies to follow Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) rules. That means everything - from how samples are stored to how data is recorded - must be traceable and tamper-proof.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is adapting to more complex drugs. Topical creams, inhalers, and drug-device combos (like insulin pens) are harder to test than pills. In 2023, 78% of complete response letters for topical generics cited bioequivalence issues.To fix this, the FDA is rolling out new tools:

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling - Computer simulations that predict how a drug behaves in the body without human trials.

- Advanced in vitro models - Lab systems that mimic skin or lung tissue to test absorption.

- Expedited review for U.S.-made drugs - The Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program gives priority review to generics made in the U.S. with U.S.-sourced ingredients.

By 2024, the FDA plans to release draft guidance for 45 complex product categories. This means more clarity - and more opportunity for manufacturers who stay ahead of the curve.

The Bigger Picture

Bioequivalence isn’t just a regulatory hurdle. It’s the foundation of affordable medicine. Thanks to the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, generic drugs are now a cornerstone of U.S. healthcare. But that system only works if every generic meets the same high standard.The FDA’s requirements may seem strict - and they are. But they’re also necessary. Patients deserve to know that the $5 generic they buy is just as reliable as the $50 brand-name version. And thanks to rigorous bioequivalence studies, they can.

What is the 80/125 rule in bioequivalence studies?

The 80/125 rule is the FDA’s standard for determining if a generic drug is bioequivalent to the brand-name version. It means the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic’s AUC and Cmax values compared to the brand’s must fall between 80% and 125%. If it does, the two drugs are considered to have the same rate and extent of absorption, meaning they’ll work the same way in the body.

Do all generic drugs need human bioequivalence studies?

No. Some generics qualify for a biowaiver - meaning they don’t need human studies. This applies to products like oral solutions, eye drops, and topical creams where the drug isn’t meant to be absorbed systemically. These products must meet strict Q1-Q2-Q3 criteria: same ingredients, same formulation, and same physical properties as the brand-name drug.

Why are narrow therapeutic index drugs treated differently?

Drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin have very small safety margins. Even a small difference in absorption can cause underdosing (ineffective treatment) or overdosing (toxic effects). For these, the FDA tightens the bioequivalence range to 90-111% to ensure much tighter control over dosing consistency.

How long do bioequivalence studies usually take?

A typical bioequivalence study in healthy volunteers lasts 2-4 weeks, including screening, dosing, and follow-up. But the whole process - from designing the study to submitting data to the FDA - can take 6 to 12 months. For complex drugs or those requiring multiple study arms (fasting and fed), it can take longer.

What’s the biggest reason ANDA applications get rejected?

The most common reason is poor study design or incomplete documentation. This includes using unreliable lab methods, not following product-specific guidances, having too few participants, or failing to properly report statistical results. Companies that follow the FDA’s detailed Product-Specific Guidances have nearly double the first-cycle approval rate.

Can a generic drug be approved without being tested in the U.S.?

Yes, but it’s harder. The FDA accepts bioequivalence data from studies done outside the U.S. if they meet the same scientific and regulatory standards. However, the Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program gives priority review to generics that are both manufactured and tested in the U.S., making it faster and more reliable to get approval.

All Comments

Mary Kate Powers November 30, 2025

It's amazing how much science goes into something most people take for granted. The 80/125 rule isn't just bureaucratic red tape-it's a carefully calibrated safety net that ensures your $5 pill does exactly what your $50 one does. I've seen patients panic switching generics, but when you understand the rigor behind it, it's a relief, not a risk.

Richard Thomas December 2, 2025

The regulatory framework governing bioequivalence is a triumph of evidence-based pharmacology. The FDA's adherence to statistically rigorous confidence intervals-specifically the 90% CI for AUC and Cmax bounded within 80% and 125%-is not merely a procedural formality, but a reflection of decades of pharmacokinetic research. To dismiss this as arbitrary is to misunderstand the foundational principles of therapeutic equivalence. The precision of these thresholds is grounded in population pharmacodynamics, not administrative convenience.

Furthermore, the application of scaled average bioequivalence for highly variable drugs represents a sophisticated adaptation to biological heterogeneity, demonstrating that regulatory science evolves in tandem with pharmacological complexity. This is not a system designed to hinder access, but to ensure that access is never compromised by efficacy.

Biowaivers under the Q1-Q2-Q3 paradigm are similarly grounded in physicochemical predictability, eliminating unnecessary human trials where systemic absorption is neither intended nor plausible. The FDA’s Product-Specific Guidance documents, numbering over two thousand, are not bureaucratic burdens but indispensable roadmaps for manufacturers seeking compliance without guesswork.

The emergence of PBPK modeling and advanced in vitro systems signals a paradigm shift toward predictive, non-clinical bioequivalence assessment. This is not a dilution of standards, but an elevation of scientific rigor. The Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program further reinforces national supply chain integrity, reducing dependency on opaque international manufacturing networks.

It is imperative to recognize that the 43% first-cycle approval rate is not a failure of the system, but a reflection of its uncompromising standards. The 68% success rate for those adhering to PSGs is not a coincidence-it is the direct result of disciplined scientific practice. Regulatory science is not about obstruction; it is about certainty.

Sara Shumaker December 3, 2025

I love how this post breaks down the science without jargon overload. But I also wonder-how many people realize that behind every cheap generic is a team of scientists working in sterile labs, running blood draws at 3 a.m., and triple-checking data because someone’s life depends on it?

It’s not just about cost. It’s about dignity. The person choosing between a $5 pill and a $50 one isn’t just saving money-they’re choosing to live without shame. And the FDA’s rules? They make sure that choice doesn’t come with a hidden cost.

Also, the 90–111% range for narrow therapeutic index drugs? That’s the difference between healing and harm. I’ve had family members on warfarin. One tiny variation in absorption and you’re in the ER. That tighter standard isn’t overkill-it’s survival.

And the biowaivers? Genius. Why test a topical cream in humans when you can prove it behaves the same on a synthetic skin model? Efficiency isn’t cutting corners-it’s doing the right thing the smart way.

Let’s stop treating generics as ‘lesser’ and start celebrating them as triumphs of public health engineering.

Tina Dinh December 4, 2025

THIS. 👏👏👏 I used to think generics were ‘cheap knockoffs’ until I learned how hard the FDA works to make sure they’re just as good. Now I only buy generics and tell everyone to do the same. 💊🌍 Save money, save lives!

Joy Aniekwe December 5, 2025

How convenient that the FDA’s ‘rigorous standards’ align perfectly with the interests of the pharmaceutical conglomerates who fund their advisory panels. The 80/125 rule? A smokescreen. The real reason generics are approved is because the brand-name companies have already exhausted their patents-and the FDA, beholden to industry lobbying, gives them just enough science to look legitimate.

Meanwhile, patients on levothyroxine are still being switched between generics that cause palpitations, weight gain, and anxiety. The 90/111 range? A joke. If it were truly safe, why do so many endocrinologists refuse to switch their patients?

Don’t be fooled. This isn’t about safety. It’s about profit.

Steven Howell December 6, 2025

As someone who has worked with international generic manufacturers across Asia and Latin America, I can attest that the FDA’s bioequivalence requirements are among the most stringent in the world. Many foreign facilities fail their first inspection-not because they’re negligent, but because they underestimate the depth of documentation required.

The Product-Specific Guidance documents are not optional reading-they are the bible. I’ve seen companies spend over $2 million and 18 months trying to get one ANDA approved because they skipped consulting the PSG. It’s not bureaucracy-it’s precision.

And while the Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program is a step in the right direction, it’s worth noting that the U.S. still imports over 80% of its active pharmaceutical ingredients. The real challenge isn’t just testing-it’s rebuilding domestic supply chains without sacrificing quality.

There’s a reason countries like Germany and Japan model their regulatory frameworks after the FDA. It’s not nationalism-it’s science.

Latika Gupta December 7, 2025

Wait, so if a drug is absorbed through the skin, like a cream, you don’t need blood tests? But what if someone has a skin condition that changes absorption? Are you telling me they just assume it works the same for everyone? That seems… risky. I have eczema and my dermatologist warned me about generic creams not working the same. Is that just anecdotal?

Mary Kate Powers December 8, 2025

Great question-this is exactly why the FDA requires IVPT for topical products: to simulate real skin conditions in the lab. Studies use both healthy and compromised skin models. If you have eczema or psoriasis, your dermatologist may still recommend the brand-name version because individual variability matters-but that’s not a failure of the generic system. It’s why doctors personalize prescriptions. The generic is still safe and effective for the majority. But medicine isn’t one-size-fits-all, and that’s okay.