When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure it actually does? The answer lies in bioequivalence - a scientific standard that bridges the gap between brand-name drugs and their generic copies. It’s not about matching ingredients exactly. It’s about proving the body absorbs and uses them the same way.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

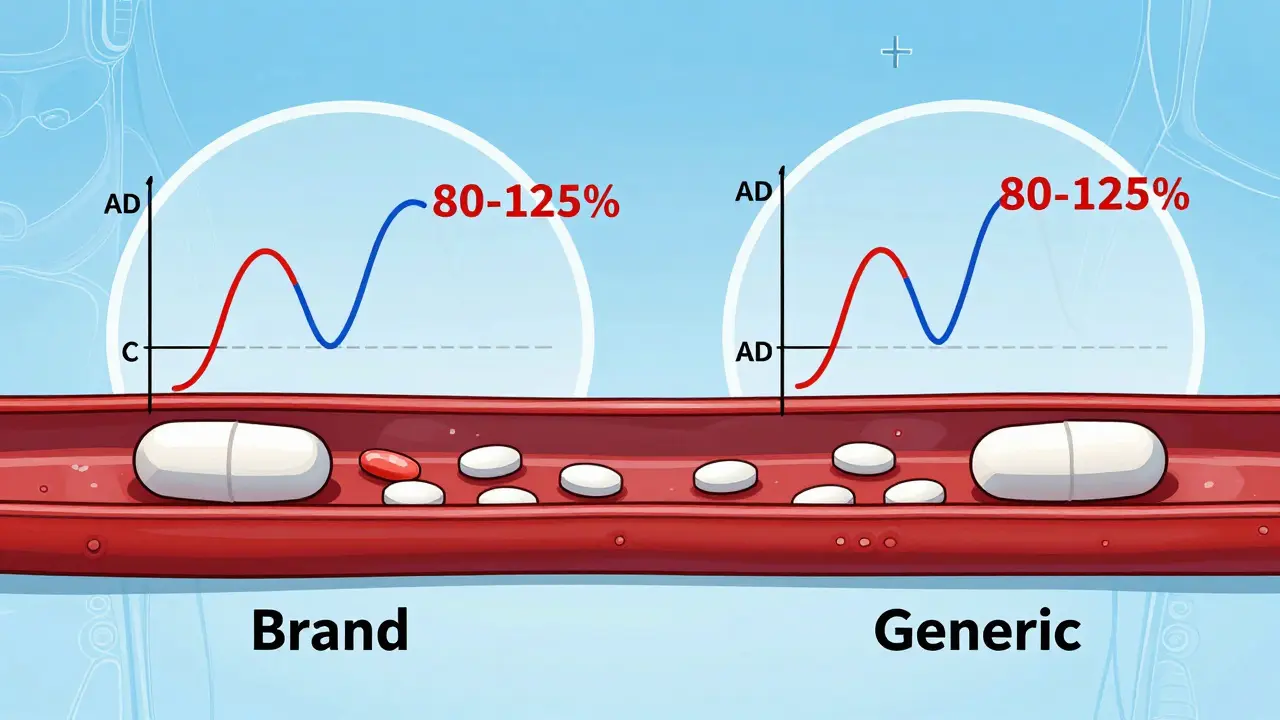

Bioequivalence isn’t about whether two pills look the same or have the same inactive ingredients. It’s about whether they deliver the same amount of active drug into your bloodstream at the same speed. The FDA defines it as the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of action. In plain terms: if you take a generic version of your blood pressure pill, your body should see the same drug levels over time as if you took the brand-name one.

This standard was created under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic manufacturers had to repeat all the expensive clinical trials done by the original drugmaker. That made generics too costly to produce. The law changed that. Now, if a generic can prove bioequivalence, it doesn’t need to redo human safety studies. The data from the brand-name drug applies to the generic too.

How the FDA Tests for Bioequivalence

The test is done in a controlled clinical study, usually with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These people take both the brand-name drug and the generic version - sometimes in a different order - under strict conditions. Blood samples are taken over several hours to track how much of the drug enters the bloodstream and how long it stays there.

Two key numbers are measured:

- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug is absorbed.

- AUC: The total exposure over time - how much of the drug your body has access to from start to finish.

The FDA requires the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand-name drug’s Cmax and AUC to fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. The average (mean) result must also land within that range.

For example: If the generic’s average AUC is 93, and the 90% confidence interval is 84 to 110, it passes. Even though 93 is lower than 100, the entire range (84-110) fits inside the 80-125 window. But if the average is 116 with a confidence interval of 103 to 130, it fails - because 130 goes beyond the 125% limit.

Common Misconceptions About the 80-125% Rule

A lot of people think the 80-125% range means a generic drug can contain anywhere from 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The rule doesn’t apply to how much drug is in the tablet. It applies to what your body actually absorbs.

Both the brand and generic pills must contain the exact same amount of active ingredient - say, 10 mg of lisinopril. The difference comes in how well your body absorbs it. Maybe the generic uses a different coating or filler that slows down dissolution. That’s okay - as long as the final blood levels end up in the right range.

Think of it like two cars driving the same route. One is a sports car, the other a sedan. They start at the same time, drive the same distance, and arrive at the same destination. But one gets there faster, the other slower. As long as both arrive within a reasonable time window, they’re functionally equivalent. Bioequivalence is the same idea.

Why This Range Works - And When It Doesn’t

The 80-125% range isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on statistical analysis of what’s considered clinically insignificant for most drugs. A 20% difference in exposure is generally too small to affect how well the drug works or how safe it is.

But there are exceptions. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - where even tiny changes in blood levels can cause side effects or treatment failure - need tighter control. Think warfarin, lithium, or certain anti-seizure medications. Even though the FDA still uses the same 80-125% standard for these, they’re monitored more closely. Doctors often prefer to stick with the same brand for these drugs, not because generics aren’t safe, but because consistency matters more.

Some studies have mistakenly claimed that generics can vary by up to 45% in active ingredient content. That’s a misunderstanding of the bioequivalence metric. The FDA doesn’t allow that kind of variation in the pill itself. The variation is only in absorption - and even then, it’s tightly controlled.

What Happens Before Approval

Getting FDA approval for a generic drug isn’t just about running one bioequivalence study. First, the manufacturer must prove pharmaceutical equivalence: same active ingredient, same dose, same form (tablet, capsule, etc.), same strength, and same quality standards as the brand.

Then comes bioequivalence testing. The FDA requires the most accurate, sensitive, and reproducible methods available. That means using validated lab techniques and well-designed studies. In some cases - like topical creams or inhalers - bioequivalence can’t be measured through blood tests. For those, the FDA allows in vitro testing: comparing how the drug dissolves or disperses in lab conditions.

Since 2021, the FDA also requires companies to submit all bioequivalence studies they’ve done - not just the ones that worked. This transparency helps catch hidden issues. If a company ran five studies and only one passed, the FDA can see why the others failed. Maybe there’s a manufacturing flaw. Maybe the formulation is unstable. This prevents unsafe products from slipping through.

Real-World Impact

Generic drugs make up about 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they cost only about 20% of what brand-name drugs do. Over the last decade, generics saved the healthcare system an estimated $1.7 trillion. That’s billions of dollars in savings for patients, insurers, and taxpayers.

The FDA reviews around 1,000 generic applications each year. About 65% get approved on the first try. The rest get deficiency letters - often because the bioequivalence data was shaky, the formulation didn’t match the brand’s dissolution profile, or the manufacturing process wasn’t consistent enough.

Companies that fail often go back, tweak their formulation, and resubmit. It’s expensive and time-consuming - which is why many generics are still priced low. The system is designed to be efficient, but not easy.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The FDA is exploring new ways to make bioequivalence testing faster and smarter. For complex drugs - like injectables, biologics, or long-acting formulations - traditional blood tests don’t always work. New tools like computer modeling and simulation are being tested to predict how a drug will behave in the body without needing human trials.

By 2026, the agency expects to approve more complex generics using these methods. That could mean more affordable options for cancer drugs, insulin, and other high-cost treatments. The goal isn’t to lower standards - it’s to meet them more efficiently.

For now, the 80-125% rule remains the gold standard. It’s simple, proven, and backed by decades of real-world use. Millions of people take generics every day without issue. The science behind bioequivalence isn’t perfect - but it’s good enough to keep patients safe, healthy, and saving money.

All Comments

Gregory Clayton January 9, 2026

This 80-125% rule is a joke. America’s healthcare system is being sold out by Big Pharma and their generic puppet masters. You think your blood pressure pill is the same? Try switching and see how your body reacts. I’ve had patients crash after switching - and the FDA just shrugs. This isn’t science, it’s corporate cost-cutting dressed up as progress.

Catherine Scutt January 11, 2026

Actually, the data’s solid. I’ve reviewed bioequivalence studies for a decade. The 80-125% range isn’t a loophole - it’s statistically sound. If you’re seeing differences, it’s likely adherence, diet, or gut microbiome, not the pill.

Alicia Hasö January 12, 2026

Let’s not forget the human impact here. Generics aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet - they’re the reason a single mom in Ohio can afford her insulin. The FDA’s system isn’t perfect, but it’s saved millions from choosing between medicine and rent. Let’s support the science that makes healthcare accessible, not tear it down out of fear.

Jacob Paterson January 13, 2026

Oh wow, so the FDA lets generics be 20% weaker and we’re supposed to cheer? Brilliant. Next they’ll say a 20% weaker airbag is ‘bioequivalent’ to the real one. You people are hilarious. This is why Americans die from preventable causes - because we trust regulators who think ‘close enough’ is good enough.

Phil Kemling January 15, 2026

It’s fascinating how we reduce biological complexity to a statistical window. The body isn’t a test tube. It’s a dynamic, adaptive system. Two drugs may have identical Cmax and AUC, but what about tissue distribution? Epigenetic responses? Gut flora interactions? The FDA’s metrics are pragmatic - but they’re not holistic. We’re optimizing for cost, not biological truth.

Diana Stoyanova January 16, 2026

Look, I get why people are scared - I used to be too. But I’ve been on generic lisinopril for six years, and my BP is better than it was on the brand. I’ve talked to pharmacists, nurses, even docs who used to swear by brand names - now they switch their own families. The 80-125% rule? It’s not magic, it’s math. And math doesn’t lie. The real villain isn’t the generic pill - it’s the fear-mongering that keeps people from saving money and staying healthy. Stop listening to the alarmists. Trust the data. Your wallet - and your heart - will thank you.

Elisha Muwanga January 18, 2026

Let’s be clear: this whole bioequivalence framework was designed by pharmaceutical lobbyists to protect their profits under the guise of ‘efficiency.’ The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t make generics cheaper - it made them *legally* interchangeable without proving real-world outcomes. And now we’re told to trust a 40-year-old statistical loophole as if it’s gospel. Shameful.

Aron Veldhuizen January 20, 2026

Correction: The FDA does not allow generics to vary in active ingredient content - that’s true. But the 80-125% absorption window, when applied to drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, is a calculated risk. It’s not that generics are unsafe - it’s that the system is designed to tolerate variability that, in rare cases, can be clinically meaningful. The real issue? We don’t track long-term outcomes of generic switches in real-world populations. We assume equivalence. We never prove it - not really. That’s not science. That’s institutional inertia.